We reframe blackness as a realm and a gift

Dante Stewart

I've not heard that song since watching "Remember the Titans" a few years back. Though I recall the night before putting Asa to sleep and skimming a bit of Alice Walker's novel "Temple of the Familiar" from 1989, Marvin and Tammy Terrell's duet came to mind.

"A true artist, as God has shown us", writes Alice Walker and describes Arvid's closed eyes, broken melodies filled with gray and witness on the guitar strings, "He knew he couldn't dare doubt the power of his songs." The memory and love linger and dance in this text as Marvin's body moves with Tammy's, the story written anew with voices uniting to tell tales of humanity's joys, sorrows, and sanctities.

The pain of remembrance lingered within Arvid's voice, but he sang nonetheless. Marvin did too, Tammy too. "His faith must be that the pain he inflicts on others and himself transforms, not destroys", wrote Walker. It is this faith in ourselves and our ability to be honest and free that comes to our aid, offering healing and wholeness in our existence.

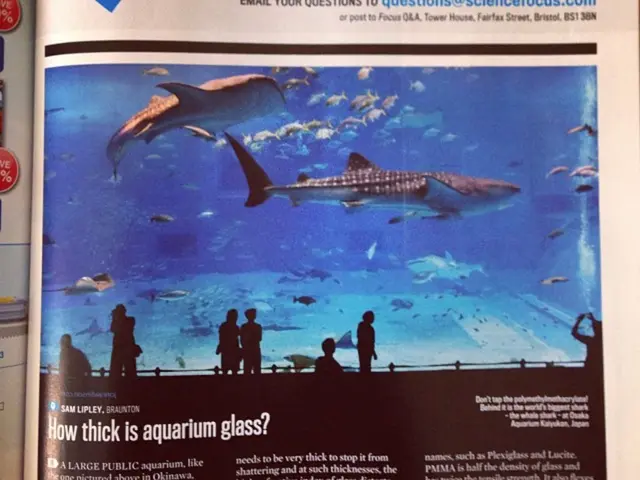

As I often remind myself of this photograph, the inherent strength of Black existence, discussions about Black Lives, Black Arts, and Black History Month often fail. People struggle to see within our perspectives, missing our movements, laughter, and song.

Let it be known, within the history of Black people, salvation of America or white people is not the concern. Our story, forged amidst a world Baldwin once described as "a loveless one," persists in a place where Black books and the exploitation of Black creativity are still banned, where Black freedom is defined by an oppressive system that inflicts harm, damages life, devalues existence -- we must remember who we are and why we tell Black stories.

While there are no single Black experiences, no one singular way of being seen or understood, the manner in which we transform the essence of what we carry is uniquely Black. Yet, many still do not recognize the myriad forms of life creation, love, and living that surpass the parameters of white imagination.

We must remember: Whites perceive Blackness as curse and sin. We redefine Blackness as world and gift anew.

Black history extends beyond the question "How do I remember and understand black people?" Instead, we question: How can we see, hear, and create a space that empowers Black people to feel seen, inspired, and protected? The world finally learns to love Black people.

Some people seem to think our lives are merely chapters offering lessons to aid white people. I cannot deny the simple truth that, in 2020, countless people visited our books, art, or streets, believing a single reading or march would somehow magically alter a deeply-rooted white supremacist structure without fundamentally changing it. We coexist.

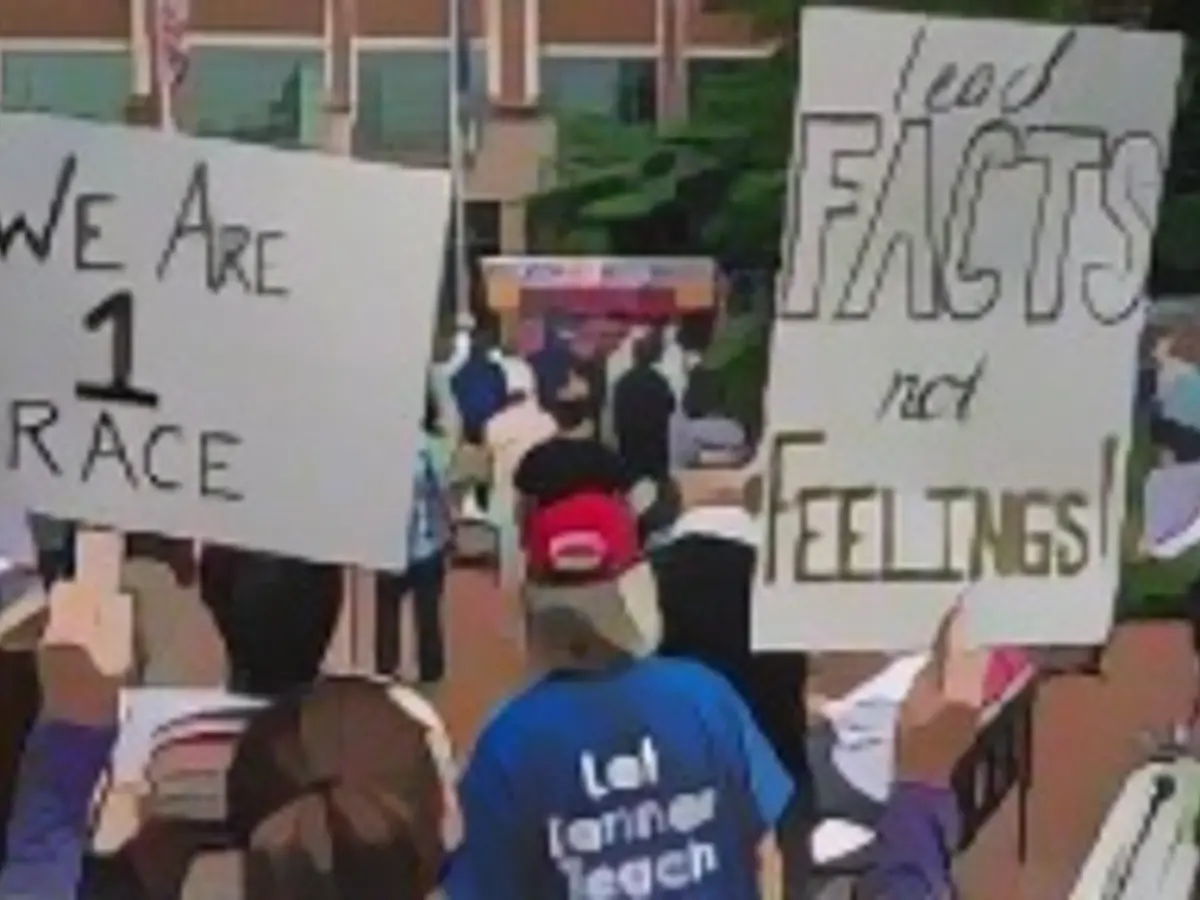

Just two years later, faced with the backlash of whites and the exhaustion of whites, we are once again confronted by the dual threat of oppression and a weariness that sees the other side. There are those who seek to erase us, and others who wish to control us.

This overlooks the strength of our existence. We do not need to be perfect or extraordinary to survive. We do not need to be "exceptional" or "superhuman." Such traits are not necessary. Our strength lies in our existence, in Baldwin's frequently underappreciated words, that we are "truly beautiful" at the end of "Letters from a Place in My Heart."

On January 25th, only two days, seven hours, and thirteen minutes after receiving the news of my great-grandfather Jonny Rubin Albert's passing, I sat in my favorite chat on FaceTime with a local café friend discussing Hanif Abdurraqib's "American Imp: Notes in Celebration of Black Performance."

I savored the tasty Black coffee, still confused by my grief and feeling a gaping hole left by the news. Opa always shared profound Socratic quotes or memories of Martin Luther King Jr.'s speeches or sayings like, "If you have a glass and a plan, I'm your man."

I drank and laughed, took another sip, laughed some more.

"He was a good man and always willing to give," I said to my friend on the screen. "I'll miss him." "He loved to dance," I said, sharing a video my brother had posted that morning, featuring my great-grandfather dancing to his favorite song "The High Is Gone."

"damned Opa," read the caption beneath the familiar Southern drawl. Following were laughing emojis, then a succession of emojis with teary eyes. The old, crippled movement of his body, mirroring Marvin's lifting arms to the sky, brought to mind a Hanif poem centered around grief, Black dance, and the sacredness of even stumbling, imperfect movement: "Now I know that true joy in dancing is seeing another world, turning the body into prayer, so time can slow down."

Husband Hanif observed things that often went unnoticed. Common Black sports deserve recognition, documentation, and remembrance.

As I read this, I wept. I needed a moment to remember, long enough to raise my voice in praise to God for such a blessed, long, and extraordinary life. Grief has a way of finding us everywhere and everywhere -- the way dancing requires us to pause, relax, and return to the dance floor more easily than we left it.

What I've learned from talking about Black lives is that loudness gives us voice and frees our bodies. It's about deep love, speaking with honesty about our pain and trauma and simultaneously revealing our complexity and beauty. Our lives belong to us -- we are sometimes angry, sometimes resilient, sometimes remember, sometimes rest, sometimes resist, sometimes redefine -- not for others, but for ourselves. It's about Black existence -- the world we create and for ourselves.

As Toni Morrison wrote in 1974, highlighting the story of Black people, "This is what we know: 'We kneel in our lives neither on bended knees nor hanging from a tree.' This part... It's a lovely dream." Dreams are not bound by others' limited perception or blindness. We've made it happen.

It is as natural and powerful as Marvin gazing into Tammy's eyes and Tammy into Marvin's, the way my eyes have observed my great-grandfather's performance, the way Hanif's eyes look upon those who write inspiring Black stories, the way Alice's words call our songs forth, and now, I write of the wondrous nature of our existence.

Join our free weekly newsletter

- Sign up for CNN Opinion's new newsletter.

- Follow us on *Twitter

- and Facebook. It doesn't matter what whites think in these moments.

Our lives are too busy.

And life is far from perfect, but it's ours.

And as ancient church sayings go, Our life will not be in vain.

Read also:

Two sentences containing the word 'opinions' are:

Our history is not concerned with saving America or whites (meaning Holyland or Western civilization at large), but rather with ourselves and our stories. Many still don't see the diverse ways Black people live, extend creativity, or live life, stretching beyond white imagination.

Despite all the antiracist work and organization, we are once again confronted by the backlash of whites and the resignation of whites two years later. Some seek our erasure, others wish to control us, ignoring the strength of Black lives.

Enrichment data:

The given article by Dante Stewart does discuss the Black identity, its representation, and its evolution in the context of Black History Month. In reference to the seminar at Salve Regina University, the evolution of Black American identity on television over the past 80 years is explored, noting the shift from stereotypical portrayals to more nuanced representations in shows like "All in the Family" and "The Jeffersons" in the 1970s. No mention is made, however, of a possible redefinition of 'Blackness' by any individual or group. To find more specific information about this, you may need to look for recent scholarly works or interviews by Dante Stewart or other relevant authors. The provided sources do not contain direct information on this topic.

Source: