Redefining Our Blackness: A World and a Gift

Dante Stewart

I've hardly listened to that song since I watched "Remember the Titans" a few years back. Though I remember that fateful night before putting Asa to sleep and the sporadic glimpses of Alice Walker's Temple of the Familiar novel from 1989, Marvin and Tammy Terrell's image lingered in my mind.

"A true artist, as God has shown him," writes Alice Walker, describing Arvida's poignant eyes and broken melodies filled with gray and testimony on his guitar strings, "He knew he lacked the courage. He questioned the strength of his songs." The interplay of memory and love pervades this text, as Marvin dances around Tammy. With multiple voices, Walker pens a fresh and honest narrative, weaving together tales of beauty, terror, and salvation in our journey to the present.

In Arvida's voice, the weight of pain resurfaced — a pain he sought to forget. But Marvin sang, too, as did Tammy. "He believed that the pain he inflicted on others and himself would not lead to destruction," wrote Walker, "But to transformation." It is this belief in ourselves and our capacity for authenticity and freedom that helps us find healing and wholeness in our existence.

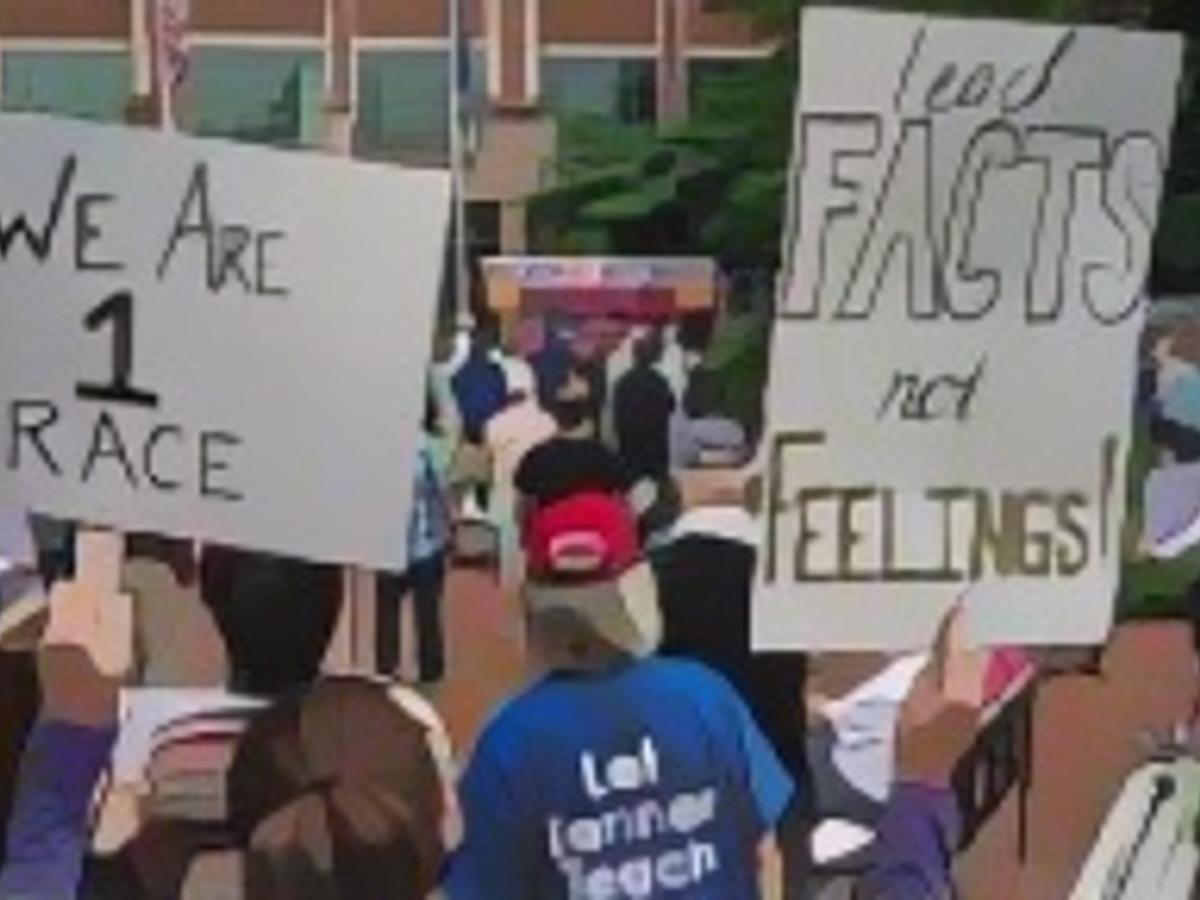

This photograph tugs at my memory: the daily power of Blackness.

Discussions about Black Lives, Black Arts, and Black History Month often fall short, as people fail to see us with our eyes. They don't see our movements, dances, calls, and songs. I've spent the past month contemplating this failure.

Let us be clear: The Black struggle is not centered on saving America or white people. The Black struggle is for us. In a moment when we still live in the world James Baldwin described as "impersonal" in The Fire Next Time — a moment when Black books and exploitation of Black creativity remain forbidden, defining Black freedom means confronting these realities: Black lives are devalued, Black art is suppressed, Black lives are hurt — we must remember who we are and why we tell Black stories.

Obviously, there is no singular Black experience. Nor is there only one way to see or understand us. However, the Black way of transforming the gift of life is singularly unique. Yet many still fail to recognize the myriad ways we create, live, and exist, transcending white imagination.

We mustn't forget that White people often consider Blackness as a curse and sin. We redefine Blackness as a world and gift anew.

Black history is more than recalling Black people or understanding them. We all ask ourselves: How can we truly see, hear, and provide a space where Black people feel seen, inspired, and protected? The world is learning to love Black people.

Some people seem to believe that our lives are merely lessons to help white people understand. I cannot deny that, in 2020, many visited our books, art, streets, and believed a simple reading or march could miraculously change the dominant white supremacist power structure without fundamentally altering it. We live together.

Two years later, after all the antiracist work and organization, we are once again confronted by the white backlash, on one hand, and white exhaustion, on the other. Some want to erase us, while others want to control us.

This ignores the power of our lives. We don't need to be perfect or extraordinary to survive. We don't need to be "exceptional" or "superhuman." Nothing is required. The power lies in our existence — in the beautiful, prosaic truth that James Baldwin articulated in his often overlooked words at the end of Letters from a Place in My Heart: "We are really beautiful."

On January 25th, only two days, seven hours, and 13 minutes after learning that my great-grandfather, Jonny Rubin Albert, had passed away and joined the Lord and his ancestors, I sat on my favorite chatting app, FaceTime, with a local café friend discussing Hanif Abdurraqib's ''American Imp: Notes on Celebration of Black Performances.''

As I swIGged down Black coffee, I was still bewildered by my grief and still felt that hole in my stomach, left by my great-grandfather's departure. He always had a deep, inspiring quote from Socrates, a memory of a Martin Luther King Jr. sermon, or a home truth like, "*If you have a glass and a plan, I'm your man*."

I laughed and sipped again. I laughed more.

"He was a good man and always had something to give," I said to my friend on the screen. "I'll miss him." "He knew how to dance," I said, and showed him a video my brother had shared that morning, where my great-grandfather danced to his favorite song "The High Is Gone."

"God d*mn Opa," captioned the video in his familiar Southern drawl. Then: laughing emojis, laughing emojis, laughing emojis. Then: emojis with tearful eyes, emojis with tearful eyes, emojis with tearful eyes. The rhythm of his faltering, aged body, almost like the way Marvin lifted his arms towards heaven, reminded me of a poem by Hanif, which speaks of grief, Black dance, and the sacredness of performance:

"Now I see that the true joy of dancing is to enter another world, to turn the body into a prayer, for time to slow down." Hanif's Husband noted things we often overlooked.

Lessons from Black sports, when recognized, documented, and remembered, add to our collective narrative.

When I read this, a wave of emotion washed over me. I needed a moment, a long moment, to remember and hold on long enough to praise God for such a fulfilled, lengthy, and spectacular life. That's what grief is: You never know when or where it will strike, but when it does, it pervades everything and everywhere. It's like dancing: You make a long pause, only to return more easily to the dance floor than when you left it.

I learned that talking about Blackness gives us a voice, frees our bodies. It's about deep love. It's about speaking truthfully about our pain, trauma, and complexity, while simultaneously revealing our richness and beauty. Our lives are our lives. We can be angry, resilient, remembering, resting, resisting, defining ourselves anew — not for the sake of others but for ourselves. It's about the Black world — the world we create and for our sake.

As Toni Morrison wrote in 1974, in an essay on the history of Black people: "This is how we know: 'We kneel neither here nor hang from trees.'" Dreams are not shackled to white people's limited imagination or vision. Other people may not see us, but we've made it.

It's as normal and powerful as Marvin looking into Tammy's eyes and Tammy looking into Marvin's, my gaze on my great-grandfather's performance, and the Black writers who write about Blackness, who see Alice writing our songs, and now I write about the wonder of our existence.

Subscribe To Our Weekly Newsletter

Subscribe to our free, weekly newsletter for exclusive content, interviews, and more. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook. We don't care what White people are thinking right now.

Our lives are too busy.

And our lives belong to us.

And, as the old hymns sing, our lives will not be in vain.

Further Reading

These two sentences contain the word:

In the history of Black people, the focus is not saving America or white people, but rather ourselves and our stories. Many people don't recognize the diverse ways we create and live life, which goes beyond white imagination.

Despite all the antiracist work and organization, we are once again confronted with the backlash of whites and the exhaustion of whites two years later. Some want to erase us, while others want to control us.

[Source: Dante Stewart's article "It's time for white America to stop pretending it understands Black pain"]

Source:

Enrichment Data

The contemporary discourse on Blackness is being redefined through several key themes and practices:

- Empowerment and Identity:

- "Cé Noir" - This term, meaning "It is black" or "This is black," symbolizes the beauty, depth, and complexity of Black identity and culture. It is used to celebrate Blackness in all its forms, serving as a term of empowerment and pride in heritage.

- Celebration of Black Excellence:

- Black History Month - This month-long celebration commemorates the achievements and contributions of Black individuals, highlighting their resilience and innovation. It serves as a reminder of past injustices and a call to action for current equality.

- Reclaiming Narratives:

- Challenging Stereotypes - The term "Cé Noir" emerged from artistic and intellectual circles seeking to redefine Black identity by challenging stereotypes and promoting a nuanced understanding of what it means to be Black.

- Cultural Impact:

- Art, Literature, and Music - "Cé Noir" has inspired countless works of art, literature, and music, fostering a sense of unity and solidarity among those who identify with its message. It has also been used to describe art, fashion, music, and literature that reflect the Black experience.

- Global Contributions:

- African Diaspora - Black History Month has expanded to include global contributions from the African Diaspora, highlighting the diversity and richness of Black culture. This includes contributions in art, science, civics, and politics, emphasizing the history of social justice and diversity.

- Resistance and Resilience:

- Celebration as Resistance - Celebrating Blackness is seen as a radical act that challenges the erasure of Black subjectivity and the violence of oppressive structures. It is a way to claim agency and refuse the negation of Black life imposed by history and society.

- Inclusive Representation:

- Diverse Narratives - The celebration of Blackness includes recognizing the diversity within Black communities, avoiding oversimplification or exclusion. This ensures that the term "Cé Noir" remains meaningful and inclusive.

By embracing these themes, contemporary discourse is redefining and celebrating the complexity and richness of Blackness, promoting empowerment, resilience, and cultural recognition.