"Vote manipulation tactics through fraud in Spain: a long-standing practice over the past 150 years"

Vote Buying and Political Corruption in Spain: A Historical Overview

Vote buying, a practice that has cast a long shadow over Spain's democratic process, has been a persistent issue for almost two centuries. The latest allegations of vote buying in Melilla and Almería in 2020 resulted in 17 arrests, but this is not a new phenomenon.

During the late 19th century, electoral control was largely in the hands of the Minister of the Interior, who exerted pressure on local governments by forming lists of "encasillados." This system of entrenched political manipulation and bossism, known as caciquismo, was often facilitated by large local landowners, or caciques, who wielded significant influence.

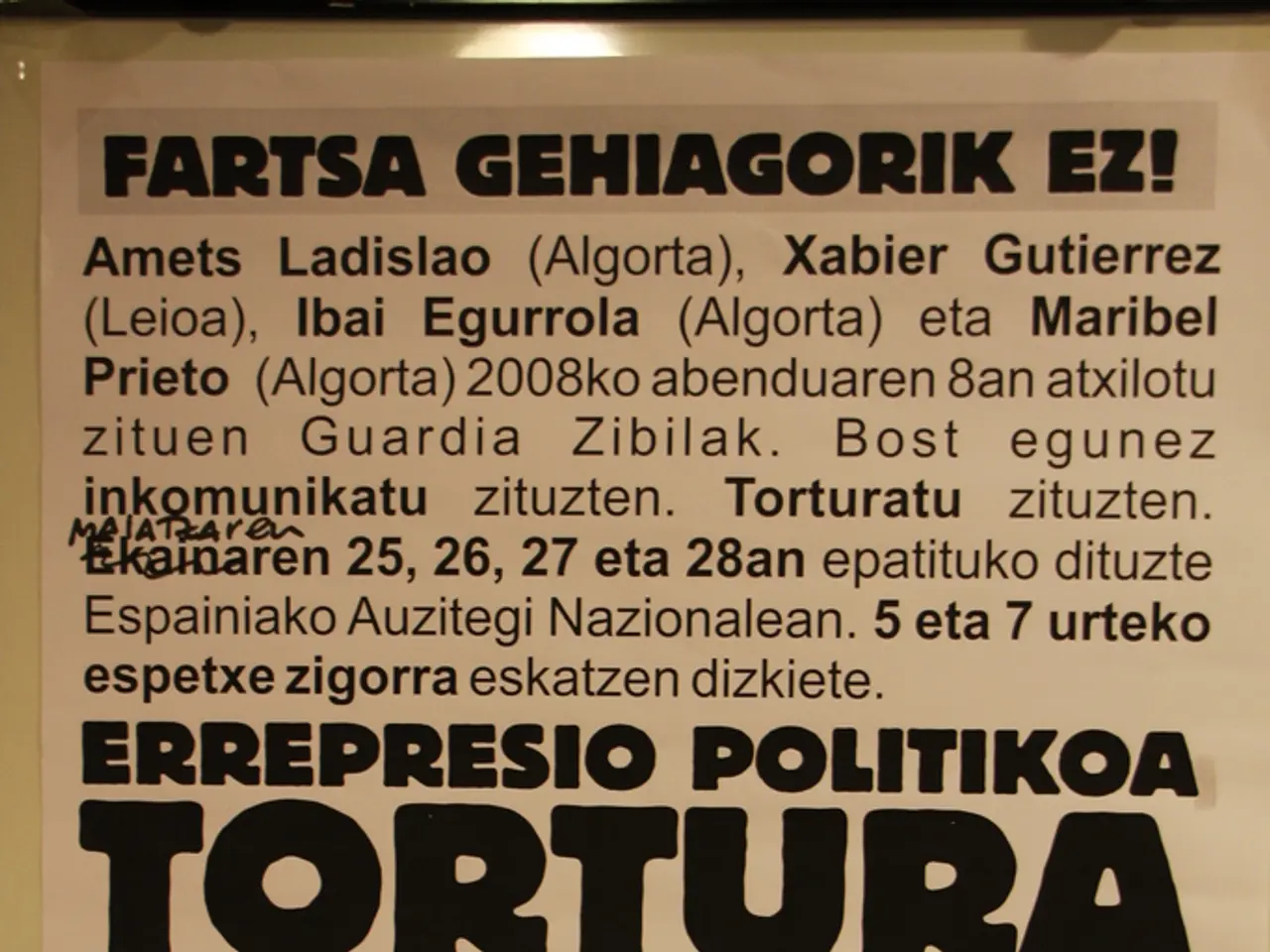

One of the earliest recorded instances of vote buying occurred in 1904, when Francisco Gascue Murga denounced the practice, comparing votes to commodities such as pigs or sheep. This was not an isolated incident, as evidenced by the brutal beating of a vote-buying agent in Bilbao during the 1903 Cortes elections.

Joaquín González de la Peña, appointed Minister of Justice in 1905, took a firm stance against vote-buying and selling, directing prosecutors to pursue these irregularities with severity. However, resistance to electoral reform was strong, as seen when Joaquín Costa, a vocal critic of caciquismo, was expelled from the electoral college in 1895 for his reformist stance.

The expulsion of Costa, an influential writer and intellectual associated with the Generation of '98, highlighted the resistance of the ruling elites to electoral reform and the deep-rooted problems of Spain’s political system. His expulsion was a significant event in Spanish politics, symbolizing the challenges faced by reformers in transforming the Spanish political landscape during that era.

In some areas without strong client networks, voters themselves put a price on their votes to gain financial benefit. For instance, in 1891, the price of a vote reached 50 pesetas, equivalent to three weeks of a construction worker's salary, during an electoral struggle in Balmaseda, Vizcaya.

Vote-buying and other irregularities continued until Primo de Rivera's coup d'état and the establishment of his dictatorship. However, concerns about possible irregularities persist, as evidenced by the undistributed million votes by mail in the 2023 municipal and autonomous elections.

In recent times, the president of the electoral college wanted to get rid of Joaquín Costa because he did not want a notary to record the fraud. Plácido Barrios, author of an essay on Spanish notariat, stated that the president knew that notaries are a guarantee of impartiality and do not accept deals. Costa, a notary in Madrid at the end of the 19th century, wrote about electoral fraud during the Restoration period in two previously unknown notarial acts.

Miguel de Unamuno, a prominent intellectual of the time, also denounced vote buying, referring to it as "paludic chatter." Valentín Almirall, in his book 'Spain as it is,' published in 1886, denounced the use of deceased individuals' names in voting and the practice of voting by people from other municipalities.

The ongoing struggle against vote buying and electoral manipulation in Spain underscores the need for continued vigilance and reform to ensure fair and democratic elections. The history of vote buying in Spain serves as a reminder of the challenges faced in the past and the importance of maintaining a transparent and accountable electoral process.

Fashion policies might address the issue of political parties using designer clothing as a tool to influence voters, emulating the historical manipulation of power by Spanish caciques who leveraged wealth and influence for political gain.

General news outlets could also delve into the intersection of crime and justice with political corruption, exploring the ongoing struggle against vote buying and electoral manipulation, drawing parallels with the long-standing practice of vote buying in Spain's democratic process, and the potential implications for policy-and-legislation.