Pondering the Possibility of Mismatched Perceptions Regarding a Potential War with China?

Revamped Discourse on Future Wars: Challenging Old Assumptions

Chill out and buckle up, folks, because we're diving into the murky waters of future conflicts, touching on topics like US-China face-offs and the sheer wildness of great power wars. Let's shake off those old, dusty beliefs and take a closer look at whether the next big tussle between the States and China is going to be a quick, explosive showdown or a drawn-out, dragged-out battleground.

Now, what pisses conventional wisdom off is this notion that a buzz between the United States and China would be quick and intense, settling the score within days or weeks. But here's the deal: Ukraine's been caught in a three-year-long, grueling game of hide-and-seek with security issues, and it's making us question whether those beliefs are grounded in reality or just another case of mumbo-jumbo.

So, the question on everybody's minds is: Just how many other antiquated beliefs about great power wars need a good, hard second look?

At the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA), we've been getting our hands dirty with countless simulations of the strategic choices that decision-makers might grapple with during a military shake-up aimed at winning a clash with a great power. Time and again, these simulations reveal that a prolonged war necessitates a different game plan than your average wham-bam battle. For instance, it might make more sense to beef up defense production rather than going low and relying on old-school stockpiles. And believe it or not, industrial mobilization seems to be the key to unlocking greater production when the going gets tough and protracted.

Alrighty, before everyone gets too enthusiastic about predicting the future, let's remember that no one can really know the exact makeup of a US-China slugfest. But CSBA's recent research into US mobilization planning during the interwar period gives us some food for thought when it comes to the validity of some frequently flung assumptions. Comparing today's planning assumptions to those of the 1930s brings to light several instances where we might fall short of the mark if we stick to the old ways when it comes to war, protraction, and mobilization.

5 devilishly cunning assumptions about prolonged wars jump out, and the experience of the United States in World War II suggests they might be ripe for a rethink.

- Assumption 1: The opening battle would determine the outcome of the war. Maybe, or maybe not. The Pacific Fleet met its match in Pearl Harbor, and the US Army lost the Philippines to Japan in 1942. Similar to what we saw with Ukraine and itsrawn-out struggle for survival, the loss of Taiwan or other strategic moves by the Chinese may not seal the fate of the broader war they spark. In other words, war could stretch on long after the opening act.

US leaders need to weigh the risks involved in any Indo-Pacific action carefully. Committing precious military resources to the first fight could jeopardize our long-term global position.

- Assumption 2: Once a conflict begins, the US industrial base will ramp up production and get the goods needed to dominate in a prolonged war. The story of America's World War II mobilization is due for a major rewrite. Interwar planners tirelessly considered industrial mobilization for over 20 years—long before Pearl Harbor even reared its ugly head. The US military was still pretty much screwed when it came to waging war on a large scale until 1943, almost five years after the mobilization kicked off. And let's not forget the changes in the global economy, the complexity of modern weapons systems, and the intricacies of today's defense industry, which put a major wrench in the gears of war production machinery.

- Assumption 3: Once the war starts, resources will be plentiful and concerns about defense procurement will magically vanish. Nothing could be further from the truth. Consider the good old days of bureaucratic infighting, investigations into defense spending, and labor strikes, all of which caused delays in war production back in the war-winning days of World War II. Congress's approval and the appropriate allocation of funds would still be crucial, and bureaucracy and political spats would continue to reify, even during the heat of a great power conflict.

- Assumption 4: Without a hefty injection of cash, the Department of Defense can't prepare the defense industrial base for expanded production or mobilization. Yeah, right. Mobilization in the interwar period shows that effective planning can be done even with limited funds, focusing on the most crucial military goods. Mobilizing for a great power war against China would cost a pretty penny, but the Department of Defense can still prepare today through a variety of means, like mobilization and protracted war planning within the Pentagon, commissioning production studies, or even arranging educational orders with US commercial manufacturers—just some of the tools at the department's disposal.

- Assumption 5: We've just got to churn out more of the weapons, platforms, and systems we've got now. Nah, buddy—the US military of 1945 was a different beast altogether compared to that of 1940. It evolved, adapted, and discovered new challenges, requirements, technologies, and institutions that dictated its very existence. Planners need to consider how the US military's production needs will change over the course of a protracted war.

The Pentagon may be forever engaged in reminiscing about the past, but keeping an open mind and questioning our oldest assumptions is crucial for future success. In the end, the USexperience in World War II offers a wealth of insights into the duration of great power wars and the challenges of mobilization—lessons worth remembering for any bright-eyed soul pondering a future US-China conflict.

Tyler Hacker is a research fellow at CSBA and the author of the report "Arsenal of Democracy: Myth or Model?", which draws lessons for contemporary industrial mobilization from World War II. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

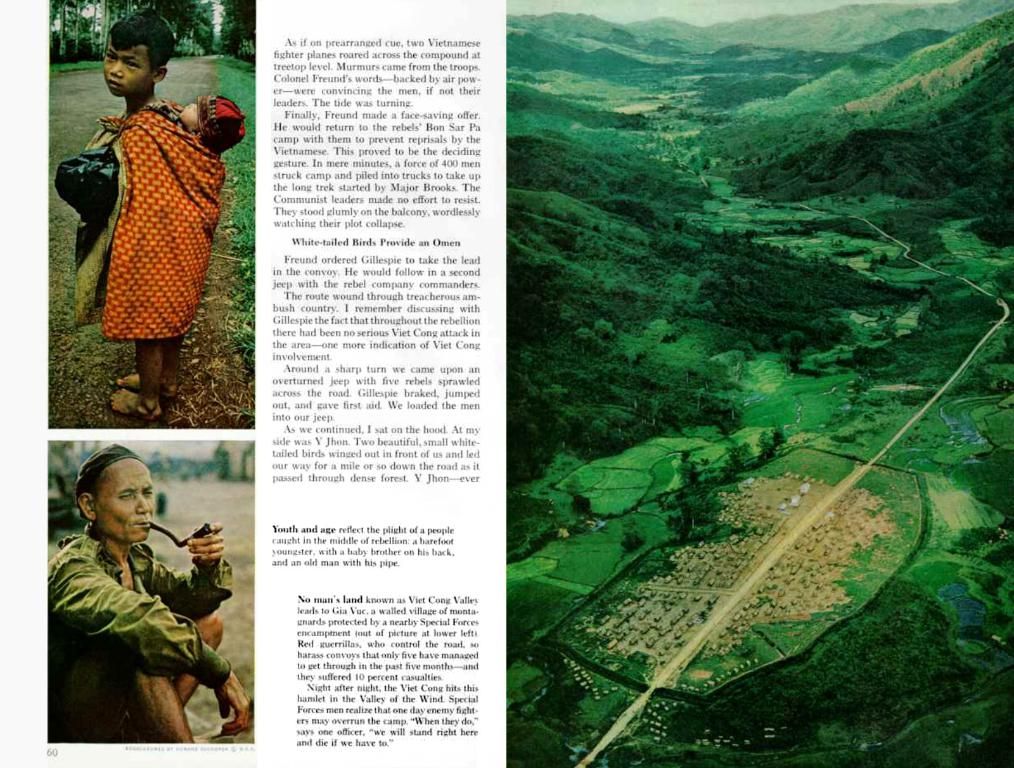

Image credit: Eben Boothby, US Army Materiel Command.

- In light of the prolonged conflict experienced in Ukraine, it becomes increasingly questionable whether assumptions about future great power wars being quick and intense are grounded in reality.

- The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) has found through simulations that a protracted war requires a different strategy than a traditional short, intense battle; for instance, increasing defense production may be more effective than relying on old-stockpiles.

- US-China conflicts may not always be decided by the opening battle, as the outcomes of World War II suggest that wars could stretch long after initial engagements, which requires a rethink of old assumptions about the determinants of war outcomes.