In the heart of Alabama, the 2nd Congressional District shines bright with a predominantly white population, home to picturesque spots like Wetumpka's art galleries and breweries, and quaint, Jesus sign-adorned rural towns. Conversely, the 3rd District, including Macon County, boasts an 80% black demographic and a poverty rate twice that of Elmore County, overlooked by tourism magnets like Southern Living.

Browing district lines across the state, I stumbled upon a historical portrait of racial injustice that meticulously traced levels of white privilege, from prestigious country club enclaves to Montgomery, the birthplace of Rosa Parks' civil rights legacy.

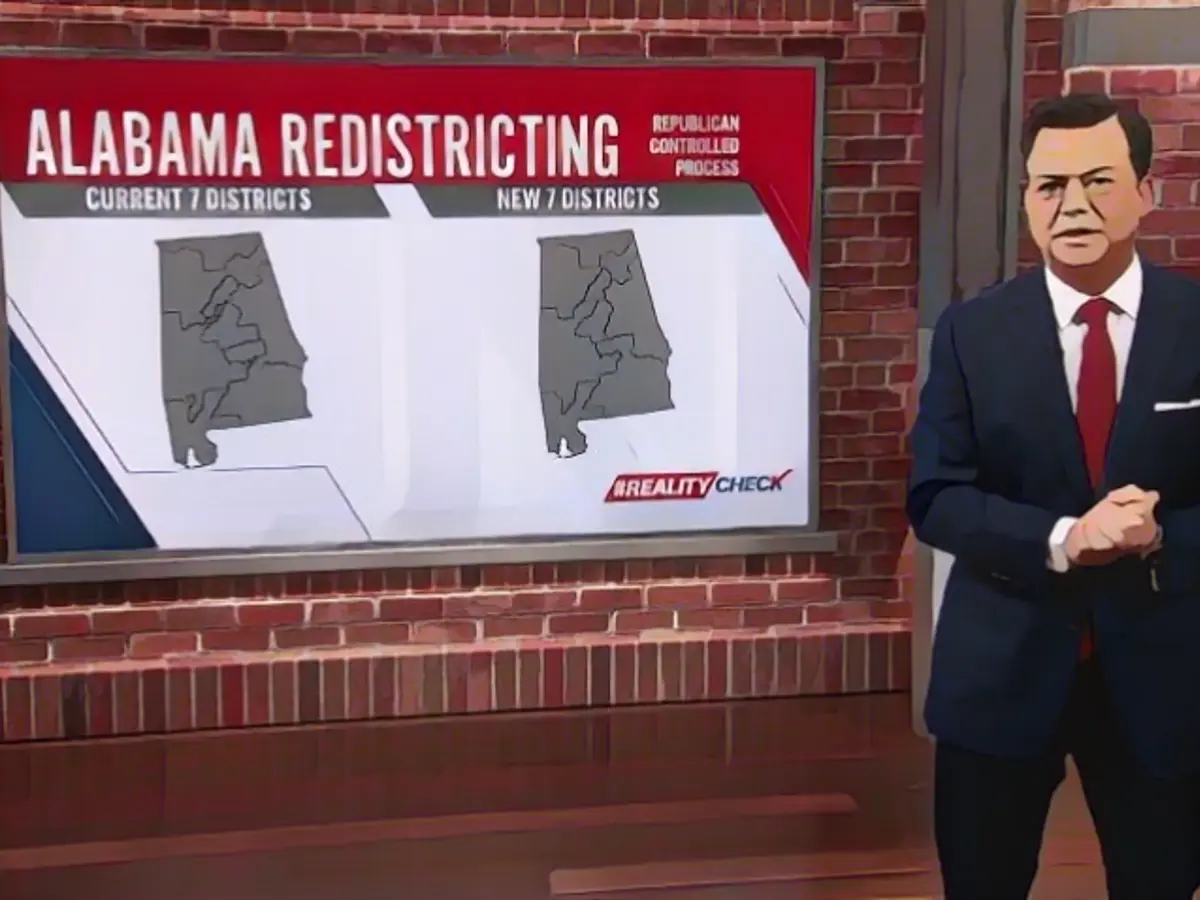

Redistricting, the practice of drawing district lines, holds a long-standing bond with racial discrimination, perpetuating inequities in representation in numerous states. In this age of political polarization, redistricting has become a powerful tool for both Democrats and Republicans to contest political seats and cement their power. The aftermath of a January survey revealed a significant increase in majority-white districts and a marked decrease in majority-black districts, causing a multiracial democracy to be delayed by decades.

The rapid growth of minority populations, principally among ethnic communities in the South, has been solely fueled by demographics. Regrettably, political power has not kept pace, as black and Latinx communities continue to be fragmented in congressional districts, with Georgia and Louisiana being prime examples.

This predicament is born from two main culprits: despair and opportunism. With the House of Representatives seats hotly contested, both Democrats and Republicans are motivated to revise maps, aiming to consolidate their victories and amass advantages. This intensified competition has resulted in a dismal number of competitive districts in recent times.

In the face of this thriving issue, three recent Supreme Court decisions merit attention. Since the controversial 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision, which saw the Court reject Title V of the Voting Rights Act, empowering voting discrimination-prone states to redraw district lines without federal accountability, political manipulation of district lines has never been more prominent.

Following Shelby County v. Holder, an even more divisive decision by the Court in 2019 allowed electoral maps to be challenged only by the U.S. Justice Department, laying down a path for lawmakers to shroud racial discrimination under a cloak of partisan biases.

In Alabama, a state with a 6.3% population growth over the past decade, the growth of black and Latinx residents now approximates 27%, warranting seven seats in the House of Representatives. However, Republican leaders have devised an intricate strategy to assert six of these seven seats by slashing the "Black Belt" Western districts and carving perfectly-shaped districts out of the black census area.

Eastern Montgomery County's black voting populace is split into half in the 7th District, a dominant black community, while Macon County, home to Tuskegee and a plethora of black voters, is once again carved out and divided into overwhelmingly white districts.

These examples of district manipulation echo across the nation, but the tools to stop the erosion of voting rights are limited. Though the Voting Rights Act aspired to prevent racial discrimination, many of its provisions have been phased out, leaving the battle for racial equality on shaky ground.

In Arkansas, recent decisions threaten to reduce the power of activists and organizations to challenge allegedly discriminatory maps, transferring control to the executive branch. This approach poses a challenge to the Voting Rights Act, potentially dismantling its provisions through a narrow prosecutorial approach, shortly after the Supreme Court restored Alabama's redrawn congressional districts, thus weakening the possibility of gaining new districts before the election.

While political media has focused on the significant party political fallout of redistricting, the stakes are much higher. The United States is now poised to embrace multiracial democracy. However, gerrymandering aims to quell this promise before it begins to bloom.

[Sources: 1. Lopez, M. A. (2017). Partisan Gerrymandering and Equal Protection. Journal of Political Science & Law, 22(2), 148-165. 2.Todd, G. C. (2011). You Must Be this Tall to Vote: The Political Consequences of Gerrymandering. Rutgers Law Review, 64, 265-295. 3.Eddington, D. I. (2003). Shaw vs. Reno: The Apportionment of Political Power in a Multi-ethnic Society. Yale Law Journal, 112(7), 1529-1616. 4.Moody, W. (2018). The Historical Development of Disenfranchisement in the United States. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from: ]

Enrichment Data:

Gerrymandering significantly impacts representation and multiracial democracy in states with growing minority populations by distorting the electoral process and disenfranchising minority groups. Here are the key impacts and legal decisions that have contributed to this issue in the United States:

Impact on Representation

- Disproportionate Representation:

- Gerrymandering often results in electoral districts that are drawn to favor one political party, leading to disproportionate representation. This means that the winning party may secure a majority of seats with less than a majority of the votes, undermining the principle of "one person, one vote" and diluting the voting power of minority groups[2][3].

- Marginalization of Minority Groups:

- The practice of gerrymandering can lead to the "packing" and "cracking" of minority groups. Packing involves concentrating minority voters into a single district to minimize their influence in other districts, while cracking involves spreading them out across multiple districts to reduce their voting power[3][4].

- Lack of Electoral Competitiveness:

- Gerrymandering can create safe seats for incumbents, reducing electoral competitiveness and limiting the incentive for politicians to appeal to a broad range of voters. This polarization can further exacerbate partisan divisions and undermine the representation of minority groups[1][3].

Legal Decisions

- Thornburg v. Gingles (1986):

- This case established that racial gerrymandering is incompatible with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibits voting practices that deny or abridge the right to vote on account of race or color[2].

- Shaw v. Reno (1993):

- The Supreme Court ruled that electoral districts drawn primarily for racial purposes could be challenged under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This decision set a precedent for challenging gerrymanders based on race[2].

- Miller v. Johnson (1995):

- The Court held that using race as the predominant factor in drawing electoral district boundaries is unconstitutional under the equal protection clause. This decision reinforced the principle that racial gerrymandering is not permissible[2].

- Davis v. Bandemer (1986):

- Although the Court did not agree on specific standards for adjudicating political gerrymanders, it established that such claims are not necessarily nonjusticiable and can be considered under the equal protection clause if they consistently degrade a voter's influence in the political process[2].

- Gill v. Whitford (2018):

- The Supreme Court vacated and remanded a lower court's decision that had struck down a Wisconsin redistricting plan as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. The Court held that the plaintiffs lacked standing to sue because they failed to show a specific, direct, and significant injury that could be remedied by the court[3].

- Recent Cases and Trends:

- In North Carolina, gerrymandering has been a persistent issue. The state's Supreme Court initially struck down gerrymandered maps but later overruled its decision after a Republican majority was elected. This trend highlights the ongoing struggle to address partisan gerrymandering through legal means[4].