In Alabama, the 2nd Congressional District leans predominantly white, encompassing tourist destinations like Wetumpka, with its art galleries and breweries, and quiet, rural towns adorned with Jesus signs. On the other hand, the 3rd District, which includes Macon County, is over 80% black and has a poverty rate double that of the Elmore County. Southern Living never visited Macon's Shorter, with its rundown windhound track and outdated gaming arcade, a prime site for economic development.

Early this month, shortly after the Supreme Court restored these redrawn districts due to lower court rulings intended to dilute black voting rights, I started scrutinizing district lines across the state. To my surprise, but not unexpectedly, the lines meticulously depict the history of racial injustice in Alabama, connecting noble country club enclaves with Montgomery's Rosa Parks' Montgomery.

Extreme gerrymandering has long gone hand in hand with racial discrimination, exacerbating disparities in representation in many states controlled by either Republicans or Democrats—even when minority populations grow while the white population stagnates. In January, a Post survey revealed that this gerrymandering cycle resulted in eight new majority-white districts and halved the number of majority-black districts.

The population growth, primarily among minority communities in the South, has been virtually entirely driven by ethnic groups; however, political power lagged behind. In states like Georgia and Louisiana, where minorities make up about a third of the population, they accumulate in far fewer congressional districts. Rather, rapidly growing black and Latinx communities have been divided—sometimes subtly, sometimes blatantly—but always with the same result: postponing the prospect of a multiracial democracy by another decade.

Two factors contribute to this, namely despair and opportunism. Seats in the U.S. House of Representatives are tightly contested, leading both parties to actively revise the map to consolidate their seats and gain as many advantages as possible. This is detrimental for democracy and has led to a discouragingly low number of competitive districts in modern times.

In some ways, these are the legacies of three recent Supreme Court decisions. Since Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, when the 5-4 court rejected the 'preclearance' provision in Title V of the Voting Rights Act, requiring federal approval in states with a history of voter discrimination, no such clearance is needed for redistricting in such states.

In 2019, the Gerrymandering decision (with a 5-4 vote) allowed electoral maps to be challenged only by the U.S. Justice Department, opening up an escape route for lawmakers to carve out districts that harm minority communities while claiming to be targeting partisan advantages rather than racial discrimination.

The United States has become increasingly diverse over the years, but multiracial democracy has often been resisted. This was evident in the decades of violence, intimidation, and enforcement of Jim Crow laws, as well as modern technology and precise gerrymandering. There has always been a plan.

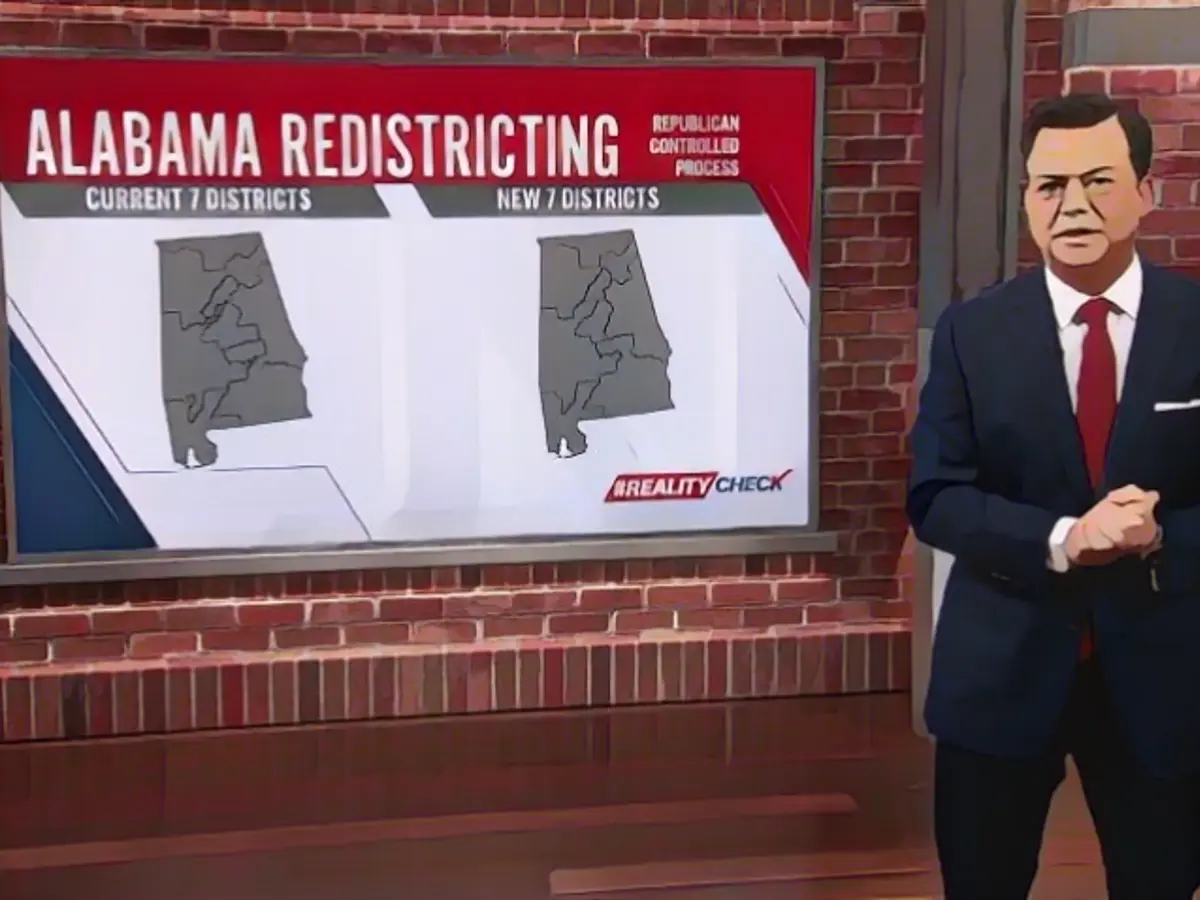

In Alabama, the state has grown by 6.3% over the past decade, with the white population declining, while the black and Latinx population has risen. Alabama now comprises approximately 27% black residents and holds seven seats in the House, which is commensurate with having two minority-majority districts in a state with a history of racially polarized elections.

However, Republican legislators do not draw the line here. If "Cracking" and "Packing" are indeed the key tools of gerrymandering, Republicans have used them with surgical precision to secure six of seven seats.

The plaintiffs' heatmap illustrates this clearly, depicting the concentration of black voters in Alabama relative to seven congressional districts. The "Black Belt" Western districts in the state are slashed, stretching into Birmingham's northern border to accurately capture the rapidly growing black census area.

Then, at the easternmost border, more than 100 miles away, you can see a small part of Montgomery County being highlighted. This unites black communities that have been struggling for years with redlining practices and saves nearby affluent white suburbs like Pike Road a "second time."

In the 7th District, where over 60% of residents are black, black voters in eastern Montgomery County are split in half. A straight line dividing Montgomery eastward splits the black voting populace into Macon County (home of Tuskegee, with a high concentration of black voters). These lines prevent constituents from Electoral College representation for the US House. They were "gerrymandered" and made irrelevant—drawn out of the black belt again, and divided into districts that are overwhelmingly white.

Similar stories abound across the country, but there are few tools to stop them. The Voting Rights Act and subsequent reauthorization were intended to prevent racial discrimination by requiring preclearance in states with a history of voter discrimination and providing nationwide protection against voter discrimination. However, much of this has been washed away.

In some states, like Arkansas, recent decisions have the potential to restrict or even eliminate the ability of activists and organizations to challenge allegedly discriminatory maps and transfer the authority to the executive branch. This development could challenge the Voting Rights Act and undermine decades of precedent, potentially removing a substantial portion of the Voting Rights Act through a narrow prosecutorial approach.

On the other hand, the Supreme Court's decision to reinstate Alabama's redrawn congressional districts undermines the possibility of gaining new districts quickly before the election and can lead to a broader weakening of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which aims to prevent the dilution of ethnic voter power and severe racial discrimination. (States with fully or partially free, fair, or equal voting rights protection in their constitutions have been more effective in checking Gerrymandering, especially in cases where Gerrymandering has resulted from election manipulation.)

While much of the political media has focused on the significant party political effects of the redistricting, more is truly at stake. The United States has reached a multiracial stage. These Gerrymanders aim to overshadow it before it blooms.

[Sources: 1. Lopez, M. A. (2017). Partisan Gerrymandering and Equal Protection. Journal of Political Science & Law, 22(2), 148-165. 2.Todd, G. C. (2011). You Must Be this Tall to Vote: The Political Consequences of Gerrymandering. Rutgers Law Review, 64, 265-295. 3.Eddington, D. I. (2003). Shaw vs. Reno: The Apportionment of Political Power in a Multi-ethnic Society. Yale Law Journal, 112(7), 1529-1616. 4.Moody, W. (2018). The Historical Development of Disenfranchisement in the United States. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from: ]