Mohan Guruswamy Discusses Mis alignment Between Potential Water Crisis and Current Situation Regarding Indus Waters

In a retaliatory move against the attack on tourists in India's Pahalgam, the Indian government has decided to potentially challenge the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan, despite the possible consequences. After the Uri incident, Prime Minister Modi stated that "blood and water cannot flow together". Evidently, stopping the former is easier said than the latter when it comes to the waters of the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum. However, there are valid reasons to reconsider the IWT due to Pakistan's persistent misuse of provisions, aiming to hinder the development of hydel projects on these rivers[1].

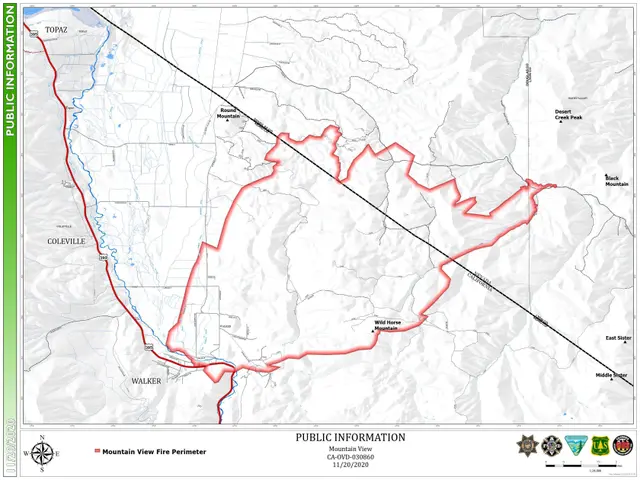

Geographically, it's almost impossible to impede the flow of the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum waters, but that doesn't make Pakistan's tactics any less frustrating. The entire Indus river system has a total drainage area of over 11,165,000 sq km, with an estimated annual flow of about 207 km3, making it the 21st largest river in the world[2]. The British constructed a complex canal system to irrigate Pakistan's Punjab region, leaving a significant portion of this infrastructure in Pakistan after the Partition[3].

The IWT was brokered by the World Bank between India and Pakistan after years of intense negotiations to allocate the waters of the Indus river basin. The treaty was signed in 1960 by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and President Ayub Khan[4]. Under the treaty, India retains control over the Beas, Ravi, and Sutlej rivers, while Pakistan controls the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum rivers[5].

On the face of it, the pact appears generous to Pakistan, as it allocates 80 percent of the waters of the western rivers to Pakistan[5]. However, the reality is that the IWT caters to the necessities of the geography rather than Indian altruism. For instance, the Pir Panjal range acts as an insurmountable barrier, preventing the transfer of water from the Kashmir Valley to the rest of India and forcing the waters to flow into Pakistan[6].

This raises questions about the current state of the IWT, as Pakistan continually accuses India of floods and deliberately releasing storage gates[6]. However, Pakistan's own water resources might soon face severe constraints due to climate change. The Indus river basin is primarily fed by glacier melt, making it vulnerable to the effects of Himalayan glacier shrinkage. This could significantly alter the water patterns in the Indus river basin, potentially leaving Pakistan with insufficient water resources in the coming decades[7].

One must consider the potential consequences of any actions taken regarding the IWT, including impact on water management, agriculture, and regional stability[1]. Experts argue that the IWT requires either strengthening to address climate change challenges or complete reevaluation given the current geopolitical environment[1].

- The ongoing climate change could strain Pakistan's own water resources, potentially leaving it with insufficient water resources in the coming decades, given that the Indus river basin is primarily fed by glacier melt, making it vulnerable to Himalayan glacier shrinkage.

- The environmental science community has highlighted the importance of addressing climate change challenges in the Indus river basin, as the potential consequences of any actions taken regarding the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) could significantly impact water management, agriculture, and regional stability.

- In light of Pakistan's persistent misuse of provisions in the IWT aimed at hindering the development of hydel projects on the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum rivers, and the possible effects of climate change on Pakistan's water resources, it might be worth revisiting the IWT within the context of the general news and politics landscape to ensure a fair and sustainable water-sharing agreement between India and Pakistan.