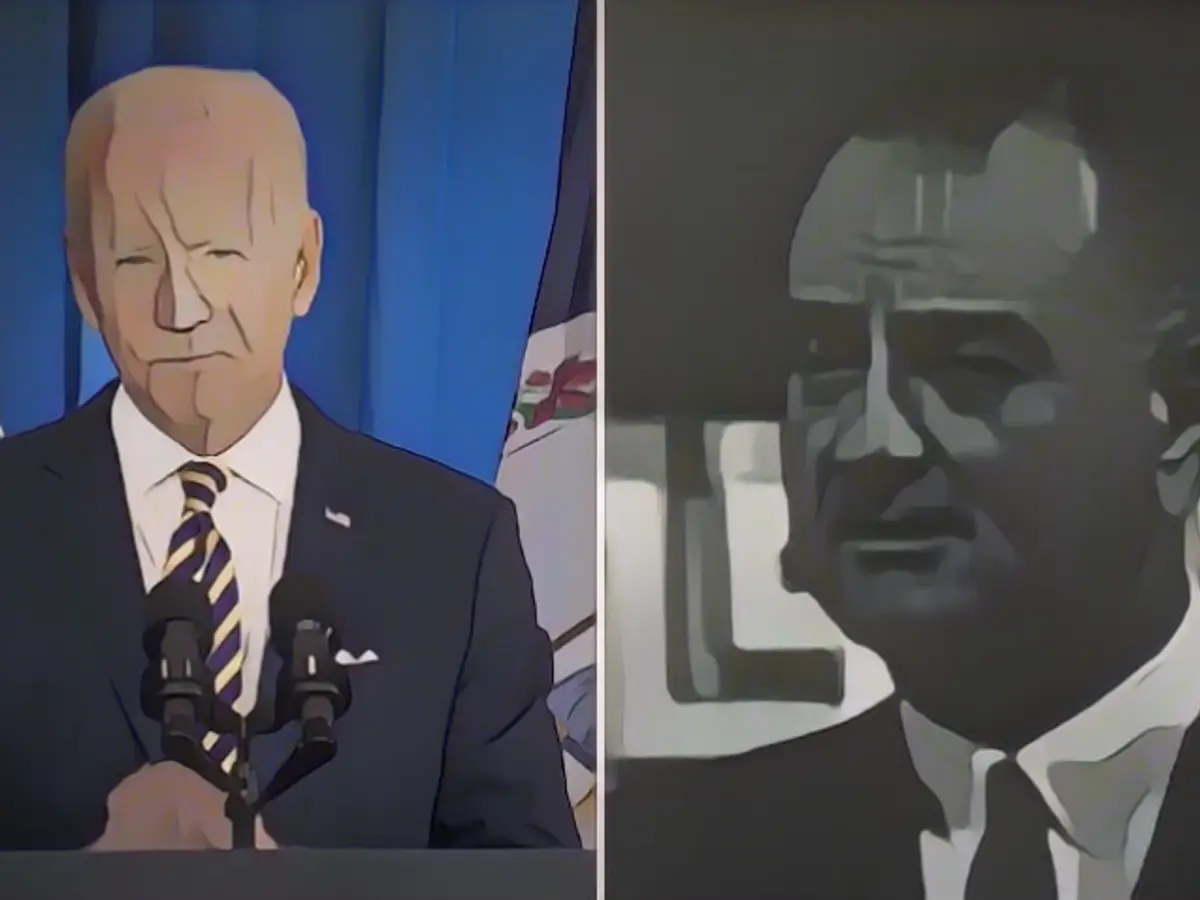

A Far Less Impressive Johnson

Tim Naftali

As we approach the elections, this comparison reveals as much about ourselves as it does about the two presidents.

The Election Before 1964

Before the elections of 1964, President Lyndon Johnson, who was set for a landslide victory, spoke to his supporters in Austin, Texas. "I have spent my entire life preparing for this moment," he said. Johnson grieved over the shocking assassination of John F. Kennedy and yearned for success during a period characterized by a powerful and growing nonviolent civil rights movement and the chilling cold war. The leadership abroad had turned to a hot war. Johnson sought to assume that type of leadership.

Although Biden's victory is not yet certain, we could forgive him if he believes that his lengthy public service in January 2021 will reach a similar high point, bringing hopes and opportunities. He was sworn in amid a pandemic that has claimed 400,000 American lives and set off months of massive, peaceful demonstrations across the nation, underscoring the urgency of ending racial injustice once and for all. And he was sworn in just days after the violent insurrection in Washington D.C., sparked by the outgoing president's refusal to accept his election loss.

Both Biden and Johnson possess the ability to face up to the great challenges of their times and believe that the American public seeks more than the pragmatism that characterized their long tenures in the Senate. Both men believe that the national trauma inflicted by their presidencies will have an attractive pull on the left.

They campaigned on platforms that were more progressive than the legislation they passed while in the Senate, and they presented more ambitious agendas than what had been proposed by the younger, charismatic, but also cautious, vice president. Johnson advocated for civil rights reforms specifically aimed at destroying the segregated South, a position he had held throughout his political career. He worked tirelessly to "bring about the Great Society," an expansion of the social safety net established by the New Deal in stark contrast to his nonpartisan stance against the cost-cutting Eisenhower administration in the 1950s.

After securing the Democratic nomination, Biden himself became a champion of the policies introduced into mainstream American politics by his more progressive former rivals, senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. Policies like student debt forgiveness, managed trade, free college, and paid family leave on a federal level, all of which have gained traction in recent years.

Yet, legislative comparisons often focus on ambition, not achievement. The similarities and differences between the two presidents tell the story of our political moment and serve as a warning of the conditions that often breed significant changes in this country.

The Next Johnson?

In a wave of legislative activity unprecedented since Franklin D. Roosevelt's first term, Johnson channeled his potential into a new relationship between the American people and the national government. When Johnson faced his first major challenge (the Congress refused to support self-governance for the District of Columbia in the fall of 1965), he had already signed the first major healthcare legislation (Medicare for the elderly and Medicaid for the poor) and a package of civil rights laws, including the Voting Rights Act, the Immigration and Nationality Act, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the Housing and Urban Development Act, the Motor Vehicle Air Pollution Control Act, the National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities Act, and parts of the 25th Amendment (regarding succession and incapacitation of the presidency).

At the beginning of his tenure, Biden sounded decidedly Johnson-esque: "The greatest risk is not doing too much, but doing too little." Prominent progressive Democrats supported his ambition and optimism – at least publicly, having conceded their earlier reservations about Biden's commitment to his agenda. House Progressive Caucus chair Pramila Jayapal told The New Yorker: "This is a progressive moment. This is a populist moment. 'This is an emergency.'"

However, after a year of hard work – including some modest successes in addressing poverty and inequality with the COVID-19 relief bill and the infrastructure bill – it appears that the president has made no progress towards achieving the accomplishments he had touted as the hallmarks of a successful progressive agenda. His "Build Back Better" cabinet had initially proposed a price tag of $3.5 trillion but continued to work on a more palatable version suitable for passage in the Senate. Last month, the president announced that the latest version, estimated to cost $1.75 trillion, would not pass due to the "persistent opposition" of senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. While there remains some hope that climate change mitigation measures may be passed as a standalone bill, there is little hope for the Equality Act, which seeks to roll back erosions of guaranteed rights from the Johnson era.

What went wrong? Some observers, like Robert Reich, former Labor Secretary under Clinton, have focused their criticism on Biden. "Now is the time for Biden to lead in the same way Johnson did in the '60s on civil rights and voting rights," Reich wrote in the spring.

Johnson used every tool at his disposal, described by Mary McGrory as "an extraordinary, powerful mix of persuasion, pressure, appeals to past favors and future rewards."

However, it is safe to say that Reich's formula will not produce the desired results this time around. To understand why Biden failed to live up to expectations and rhetoric, we must know what made Lyndon Johnson and the liberal legislative achievements of 1965-67 possible. They stemmed from Johnson's landslide victory over Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964, with Johnson securing 61 % of the popular vote and 486 electoral votes. In the South, Goldwater was popular for his resistance to federal civil rights legislation, but outside the South, Goldwater won barely any congressional districts. This was the highest level of Democratic support since Roosevelt's time of maximum power.

Moreover, Johnson had made agreements contingent on the expansion of his control over the Senate, from 68 to 32 senators, and a 37-seat gain in the House and a majority of 295 to 140. Thisnow gave the Democrats their strongest position since a generation, breaking through the tradition of bipartisanship in Congress. The conservative coalition in Congress consisted of at least 100 Southern Democrats and more than 100 Republicans from the Midwest and West in the House. The newly elected Johnson, a Democrat from outside the South, supported a liberal legislative agenda.

Controlling the Senate

Johnson eagerly seized this opportunity. After the 1959 and 1960 sessions, Johnson served as Senate Majority Leader and the Democratic Party's vice-presidential nominee, using what became known as the "Johnson method" to understand the pressure points of every legislative leader and convince them that election-winning strategies depend on supporting progressive policies, as long as Southern filibusters in the Senate and Eisenhower's veto power could prevent liberal legislation from succeeding. As president with a larger liberal faction among Democrats, Johnson would attempt this strategy again.

"Now, your boundaries are unlimited," Johnson told his young vice-president Hubert Humphrey in a conversation in March 1965, as their administration began promoting the Great Society: "It's all there. That's our agenda; that's our plan. You're half of it, and you're there every day. If you can, help us. If you succeed...you can say 'We passed education. We passed Appalachia. We passed healthcare.'" If you give me that, in two years, I'll get a majority.

Sooner or later, a miracle happened. According to Evans and Novak's book about Johnson, the 89th Congress in 1965 approved 68.4% of Johnson's proposals, up from 27.2% in 1963, the year before Kennedy's inauguration.

As my CNN colleague Julian Zelizer points out in his insightful book "The Urgency of Now," this success was not due to Johnson's charisma or leadership, but rather his newfound power. Zelizer calls for a less "Johnson-centered" perspective and emphasizes the importance of Johnson and the Democratic Party's mandate, which they earned on the campaign trail and at the polls in 1964.

In 2020, Biden had a decisive victory over Trump, but he was not overwhelming; he received 51.3% of the popular vote, not 61%. His victory was not a landslide; it lacked the public support that Lyndon Johnson's did in 1964. Even Pelosi's Democratic faction has dwindled in size by 13 seats to 222. Schumer will be the Senate's senior leader, but the Senate is evenly divided 50-50. Like Barry Goldwater in 1964, Trump triumphed in 210 congressional districts, meaning that the representatives of these districts have little incentive to challenge the new "sheriff in town."

There are, of course, other political obstacles for Biden. Despite the split between whites who supported Johnson and liberal Democrats, Johnson's agenda had the support of a majority in Congress. He could rely on the crossover votes of liberal Republicans in the House and Republican supporters of civil rights legislation in the Senate. In the House of Representatives, 30 Republicans and 112 Democrats supported the Voting Rights Act, while 70 Republicans and 13 Senators voted "yes" on Medicare.

When the Congressional Progressive Caucus, led by Pelosi with 95 of 222 House members, delayed the bipartisan infrastructure bill in the Senate until all Democratic senators agreed to a 2 trillion dollar version of the "Build Back Better" Act, Speaker Pelosi was unable to fill this vacancy with Republican votes.

What was Biden's missed opportunity? Part of the answer lies in understanding how Johnson and the liberal legislative achievements of 1965-67 were possible. They hinged on Johnson's newfound power and Johnson's ability to find common ground with Southern Democrats, who sometimes supported his anti-poverty programs as a means of helping their constituents.

Biden, whose Senate career was defined by pragmatic compromises, enjoys little trust from the left. But the all-or-nothing strategy may be Biden's way to gain that trust – even if the strategy itself has no chance of legislative success.

It's not 1965

In a sense, this strategy may not be Johnson's moment, but it could be a moment for Biden and the progressive wing of the Democratic Party. In the first week, the 117th Congress passed a comprehensive pandemic relief bill with provisions addressing some social inequalities temporarily. Despite a partisan effort to dilute the bipartisan infrastructure bill to $1.2 trillion, it remains the largest capital investment in transportation and communication infrastructure in 60 years. Biden continues to pursue more.

However, Biden could not make progress. The comparison with LBJ is revealing. Sixty years ago, Johnson defeated Republican Barry Goldwater with 61% of the popular vote and 486 electoral votes. Outside the South, Goldwater won barely any congressional districts, marking the highest level of Democratic support since FDR's heyday.

Moreover, Johnson had made concessions before taking office. Through the expansion of Senate majority, Dems gained two more seats (from 68 to 32), and 37 more seats in the House (295 to 140) and a majority of 295 to 140. The Southern Democrats and Republicans in the Midwest and West provided essential conservative coalition votes in the House. Johnson, as a non-Southern Democrat, championed a liberal legislative agenda.

But this is not 1965. The strategy may not work for Biden. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, sounds optimistic about Biden’s agenda, believing that a coalition of progressives could emerge, potentially outdoing the conservative coalition of the past. "I think we can find common ground," she told The New Yorker.

The Untold Story of Biden's Missed Opportunity

Why did Biden miss the mark in 2021, failing to live up to expectations and rhetoric? Part of the answer lies in understanding the differences between the power of popular support and legislative achievements. Clinton's secretary of labor, Robert Reich, has suggested that Biden needs to channel Johnson's approach to civil rights and voting rights if he is to produce significant legislative achievements in the domains of climate change and social justice.

However, Johnson was unable to fully deliver on these commitments due to opposition from Southern Democrats. Johnson's response was to target Northern Republicans and some moderate Southern Democrats with antipoverty programs, such as the Appalachian Regional Commission, the Office of Economic Opportunity, and the Model Cities Program. Johnson's mixed approach, which saw him both expanding social welfare and promoting civil rights, effectively mitigated the potential for a full-scale backlash from Southern Democrats.

Biden, on the other hand, has faced challenges from both sides. His pragmatic tendencies and his compromising style have yielded little trust from the progressive left and have failed to create a broader coalition that could sway more conservative legislators. The compromise bill that passed in the Senate, the Inflation Reduction Act, faces significant opposition from both progressives and conservatives. It includes provisions to promote clean-energy technologies, lower prescription drug prices, and extend medical insurance subsidies, but it falls short of tackling the root causes of climate change and fails to significantly address income inequality.

Biden's inability to build a broader coalition has also been exacerbated by the fact that he entered office with a Democratic majority in Congress that was far less powerful than Johnson's. The 117th Congress is divided, with only a slim majority for the Democrats in both the House and Senate. Additionally, the conservative block is larger in the Senate than it was during Johnson's tenure, making it even harder for Biden to pass legislation.

Furthermore, the progressive left has been frustrated by Biden's failure to deliver on campaign promises and his willingness to compromise in the face of conservative opposition. The mixed messages coming from the White House and Congress have further complicated Biden's efforts to build coalitions and deliver a comprehensive legislative agenda.

Ultimately, Biden's missed opportunity is rooted in his struggle to navigate the complex dynamics of Congress and the broader political landscape. His pragmatism and reluctance to embrace a more radical agenda have limited his ability to build coalitions, which has resulted in a watered-down legislative agenda that fails to meet the demands of the progressive left and faces strong opposition from conservatives.

As Biden approaches his second year in office, it remains to be seen how he will respond to this missed opportunity. If he is to succeed in passing substantial legislation, he will need to find a way to bridge the gap between progressives and moderates, and build a broader coalition that can overcome opposition from the conservative block in Congress. Only time will tell whether Billy can rise to the challenge.

References:

- Evans, R., & Novak, R. (2002). Lyndon B. Johnson: Portrait of a Politician. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Reich, R. (2021, May 01). Biden must channel Johnson's leadership on civil rights and voting rights. NBC News. Retrieved from

- Zelizer, J. (2022). The urgency of now: White identity politics and the collapse of the liberal order. New York: Basic Books.

Source:

Enrichment Data:

Lyndon B. Johnson's presidency and Joe Biden's presidency differ significantly in terms of legislative achievements and challenges, reflecting the distinct historical contexts and policy priorities of their times.

Lyndon B. Johnson's Presidency

Legislative Achievements: 1. Civil Rights Act (1964): Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, which was the most comprehensive and far-reaching legislation of its kind in American history. It prohibited racial segregation and discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and union membership, and guaranteed equal voting rights[1]. 2. Great Society Program: Johnson's domestic agenda, outlined in his commencement address at the University of Michigan in May 1964, aimed to create a "Great Society" characterized by abundance and liberty for all. This program included measures to fight poverty, such as the Job Corps and Head Start programs, new civil rights legislation like the Voting Rights Act (1965), and healthcare programs like Medicare and Medicaid[1]. 3. Voting Rights Act (1965): This act outlawed literacy tests and other devices used to prevent African Americans from voting, further advancing civil rights[1]. 4. Medicare and Medicaid: These programs provided health benefits for the elderly and the poor, respectively, marking significant advancements in healthcare policy[1].

Challenges: 1. Vietnam War: Johnson's presidency was also marked by increasing American military involvement in the Vietnam War, which began during the Eisenhower administration and was accelerated by President Kennedy. This conflict became a major challenge and a source of controversy during Johnson's term[1]. 2. Domestic Opposition: Despite significant legislative achievements, Johnson faced strong opposition from Southern Democrats and Republicans on issues like civil rights, which led to prolonged filibusters and other legislative hurdles[1].

Joe Biden's Presidency

Legislative Achievements: 1. American Rescue Plan Act: Signed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, this $1.9 trillion bill provided one-time payments for lower- and middle-income Americans, extended unemployment benefits, and funded coronavirus testing, contact tracing, and vaccine distribution[2][3]. 2. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act: A bipartisan $1 trillion infrastructure bill that covered transport, utilities, and broadband infrastructure[2][3]. 3. Inflation Reduction Act: This act incorporated elements of the Build Back Better Act and included provisions to promote clean-energy technologies, lower prescription drug prices, extend medical-insurance subsidies, and increase federal tax revenue[2][3]. 4. Climate Change Initiatives: Biden pledged to double climate funding to developing countries and reached agreements with the European Union and China on greenhouse gas emission reductions. He also protected millions of acres of land and ocean from natural resource exploitation[2][3].

Challenges: 1. COVID-19 Pandemic: Biden's presidency was significantly impacted by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, requiring swift and comprehensive responses through legislation like the American Rescue Plan Act[2]. 2. Economic Challenges: Biden faced elevated inflation rates and record levels of illegal border crossings, which were major concerns throughout his term[2]. 3. Foreign Policy Challenges: The withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Russian invasion of Ukraine posed significant foreign policy challenges, requiring diplomatic efforts and economic sanctions[2]. 4. Domestic Politics: Biden's approval ratings declined due to public frustration over supply chain shortages, the cost of energy, and inflation. His age and health also became a subject of public scrutiny, ultimately leading to his decision not to seek reelection[2][3].

Comparison

- Historical Context: Lyndon B. Johnson's presidency was marked by the tumultuous 1960s, including the Civil Rights Movement and the escalation of the Vietnam War. Joe Biden's presidency, on the other hand, was characterized by the COVID-19 pandemic, economic recovery efforts, and significant foreign policy challenges.

- Policy Focus: Johnson's Great Society program aimed to address poverty, racial injustice, and social welfare, while Biden's legislative agenda focused on economic recovery, infrastructure development, and climate change mitigation.

- Legislative Achievements: Both presidents achieved notable legislative milestones, but Johnson's impact on civil rights and social welfare was unparalleled in American history. Biden's achievements in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic and promoting climate action were substantial but faced more partisan opposition.

- Challenges: Johnson faced intense domestic opposition and the burden of escalating the Vietnam War, whereas Biden navigated the complexities of the COVID-19 pandemic, economic recovery, and foreign policy crises.

In summary, while both presidents achieved notable legislative successes, their presidencies were shaped by different historical contexts and policy priorities. Johnson's impact on civil rights and social welfare was transformative, whereas Biden's efforts in addressing the pandemic and climate change were significant but faced more contemporary challenges.