Can air travel's environmental impact be minimized without a guilty conscience? As the aviation industry contributes around 2.5% of global carbon emissions, its actual climate impact, due to emissions of other greenhouse gases and the formation of heat-trapping vapor trails, is actually higher. Boeing predicts a continuous growth in air travel demand, with the global commercial aircraft fleet doubling by 2042 to meet this demand.

"Air travel's problem, measured by CO2 emissions, isn't just that it's increasing, but it's also challenging to decarbonize," said Gary Crichlow, Business Analyst Director at AviationValues. "The core of the decarbonization challenge is that we haven't yet found a carbon-free energy source that can replicate the energy density, cost, safety, and reliability of jet fuel needed for global aviation."

Middle and long-haul flights, responsible for 73% of CO2 emissions in aviation, contribute heavily to climate change. According to the Aviation Environment Federation, a British non-profit monitoring the environmental impacts of aviation, a London-to-Bangkok return flight creates more emissions than a year of vegan diet savings.

As the climate crisis continues, concerns about long-haul flights affect travel choices for many, prompting more people to opt for less disruptive options near their hometowns. Yet, the question arises: is a guilt-free, truly sustainable long-haul flight even possible?

Exploring sustainable alternatives

The industry aims to achieve net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050, meaning they aim to minimize pollution, and remove any remaining emissions from the atmosphere. However, achieving this requires innovative technologies, such as sustainable jet fuel, electrical vehicles, and hydrogen power.

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) is an alternative jet fuel that can reduce CO2 emissions by up to 80%. It has a low carbon footprint, being typically produced from sustainable feedstocks like waste oil, algae, and water. While burning SAF still releases CO2, its production results in fewer CO2 emissions compared to traditional jet fuel, made from fossil fuels that release previously-bound CO2.

SAF can be produced from various sources, including algae, water, and even waste materials like used cooking oil. Short-term, the most promising SAF source is now waste oil, according to Çınar.

"It can be transformed into kerosene equivalents using certain chemical processes," she explained. "Jet fuel is also a type of kerosene, and given their similarities, SAF can be used with existing jet engines without modification."

However, despite IATA's hopes slimming down aviation's carbon footprint by 65% using SAF by 2050, its wide-spread adoption is slow due to its high cost – 1.5 to 6 times the cost of regular kerosene. A price reduction requires an increase in production and political pressure, which could take years. Moreover, existing regulations currently prohibit operating straw-turbofans with 100% SAF.

"We're forming partnerships and trying to influence policy, but the SAF mixing limit is currently at 50%," said Ryan Faucett, Boeing's Director of Environmental Sustainability. "The beauty of SAF is that its 'drop-in' nature is proven – no changes are required. The challenge now is finding a mixture with a higher SAF content."

Both Boeing and Airbus, making up more than 90% of the global commercial aircraft market, have stated that all new aircraft models will be SAF-compatible by 2030. Current technologies are currently being tested. The first 100% SAF-powered transatlantic flight took off on November 28, 2023, under the leadership of Virgin Atlantic.

Hoping for hydrogen

Though SAF still emits CO2 when burned, hydrogen seems to be the most promising technology to achieve zero emissions – a clean-burning fuel that reduces emissions of harmful exhaust gases but is not wholly eco-friendly.

"Small hydrogen aircraft may enter service as early as mid-2030s," said Professor Andreas Schäfer, lecturer at the University College London. "But for larger aircraft, we might have to wait until 2040 or later."

Some hydrogen-powered aircraft might debut earlier, as several companies worldwide work to retrofit existing aircraft with hydrogen fuel cell technology, such as Cranfield Aerospace, which plans to modify its fleet by 2024 and conduct test flights with a converted Britten-Norman Islander.

"The fuel cell in the vehicle's body holds the hydrogen, which is converted into electricity, powering the electric engines," explained Schäfer.

However, large-scale hydrogen aircraft require significant changes in materials technology, particularly in storing hydrogen's low temperature practice - -253 degrees Celsius or -423 degrees Fahrenheit – to minimize heat loss and evaporation. To store hydrogen onboard, the tank's surface area must be minimized to minimize heat loss and evaporation, which in turn requires compacting tank sizes inside the aircraft's structure, creating a technical challenge. Despite these challenges, experts agree that hydrogen will prove viable once these challenges are overcome.

"When hydrogen is used in larger aircraft, they will actually be emissions-free," said Çınar. "However, it requires significantly more space than traditional jet fuel, which means we need to reconsider aircraft design."

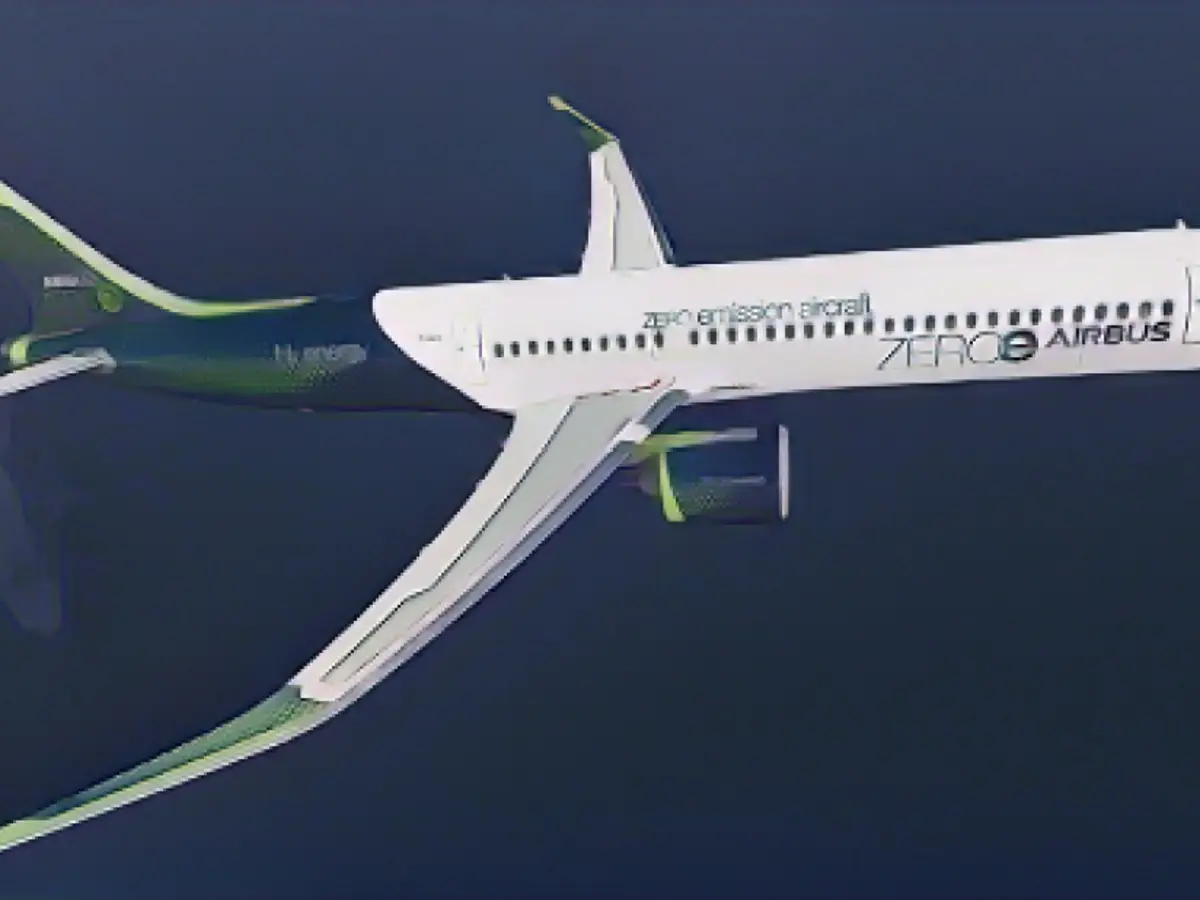

Airbus is actively involved in developing hydrogen engines and testing. "We aim to have hydrogen aircraft in operation by 2035," said an Airbus spokesperson to CNN. "In the short term, we're focusing on technological advances, but we see hydrogen as having the potential to significantly reduce aviation's climate impact."

In 2020 Airbus presented a series of hydrogen-powered concept aircraft, including a traditional aircraft in tube wing form, capable of carrying up to 200 passengers, and a radical "hybrid wing" aircraft with integrated primary structure in the main aircraft body. Other companies are working on the design, such as JetZero, aiming to deploy a hybrid-wing aircraft by 2030, which they believe could reduce operational costs by 50%.

Boeing has yet to jump on the hydrogen bandwagon, though. "We have extensive hydrogen tank expertise – for NASA's Space Launch System," said Fawcett, referencing the rocket propelling the Artemis Moon mission. "However, building and certifying hydrogen tanks for commercial aviation is not without challenges. Hydrogen takes up room, is hard to contain, and transport. For medium and long-haul flights, we won't consider hydrogen as a primary source of energy until after 2040."

Instead, Boeing predicts a combination of more efficient engines, improved aircraft designs, and operational efficiency to meet the industry's goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

"We're working with regulatory authorities to find technologies enabling more efficient flight routes, which should reduce fuel consumption (and emissions) by 5-10%," said Fawcett. "For long-haul flights, we see sustainable aviation fuel as a 'big player' for major airlines."

Fawcett added that the aviation industry has a chance to market these multi-faceted, sustainable flights using marketing campaigns promoting the flights' adoption of 100% SAF.

"I believe we'll see these changes in the next five years – first with SAF demonstrations on long-haul routes and then with regular service," he said.

"Our goal is to have the aircraft operational by 2030, and I believe the supply chain will also support these flights."

As energy sources continue to advance, Faradair Aerospace in the UK is currently developing an aircraft design that offers maximum efficiency regardless of the fuel.

"The beauty of designing for fuel flexibility is that you don't worry about impending fuel policy changes," said a Faradair spokesperson. "Our aircraft's design emphasizes multifuel capability to accommodate various energy sources as they continue to evolve."