Four million individuals flocked to see the Obama portraits – that's why.

Portraits are akin to real people in their complexity. They require more than just digital images and personal interaction; they necessitate deep reflection on how artists bring their models to life.

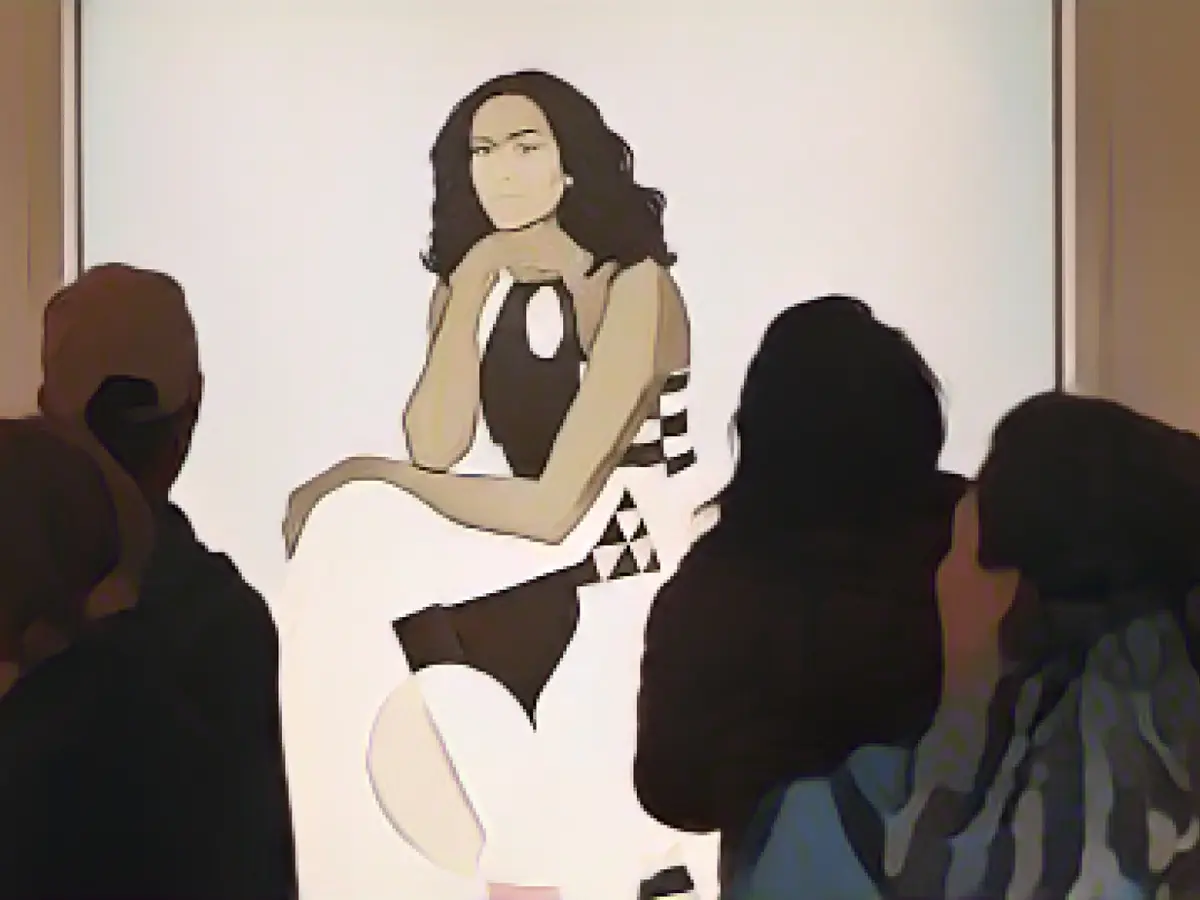

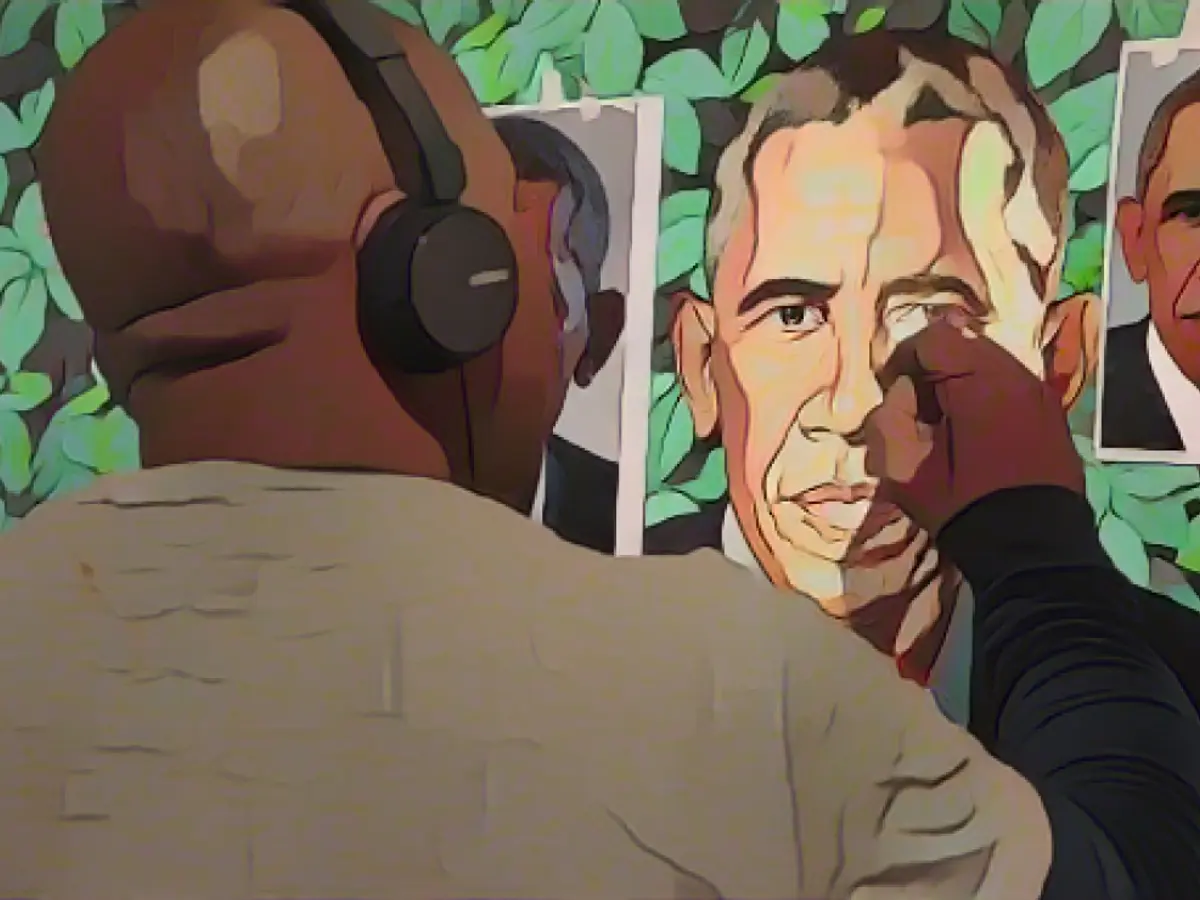

Recently, I wrote an article for a new book entitled "Obama Portraits," where Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald discuss their creations of former President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama's portraits. These paintings made quite an impact and gained unprecedented popularity. Approximately 4 million people trooped to the National Portrait Gallery, where I serve as director, to view the works of art, with visitor numbers nearly doubling since their revelation in 2018.

The question is why? Visitors know who Obama and his wife are and what they look like. Digital images of the portraits were readily available to them on their smartphones and laptops.

An online review of Wiley's Obama portrait provided an explanation: "The colors are breathtaking, but they don't do justice to the digital photos I've seen in the media." The review stated, "As shown, you can only truly experience portraits when you lift your head from the device in your hand and behold the original." Regardless of how many reproductions one sees online, the original art is always much deeper in meaning.

Probably this is the reason why millions flocked to see the originals and why presumably millions more will follow suit when the portraits embark on a nationwide tour next year. Museums, as places of confinement for strangers in society, may also play a role in fostering reflection. (Arnold Van Gennep, the French ethnographer, referred to as "Liminality" a "between" moment of social or personal transformation.)

In particular, the Portrait Gallery provides people a place to take a break from their busy lives and connect with two individuals they admire, either alone or in company of others, before returning to the "impersonal rhythm" of life.

I believe, however, that another force turns the museum into a meaningful place for social interaction, and that is technology – or better said, its absence.

Ironically, it's the physical likenesses rather than the pixels that make Barack and Michelle Obama's "visit" seem real. Often visitors took selfies in front of the portraits as souvenirs of their visit, but I observed with interest that many of them then put away their devices and conversed with each other.

Furthermore, it's the shared experience of observing Obama's portrait that prompts people to reverse the trends described in James McWilliams' article "Saving Yourself in the Age of the Selfie": reduced attention spans and "look down, look down.". "If someone looks at their phone while talking with someone else." As McWilliams noted, "An authentic self cannot exist in two places at once," and he emphasized that true friendships begin in a specific social space that requires one's full attention. Then, true friendships stand a better chance of success.

In the case of the Obama portraits, visitors must engage their intellect and heart to establish personal connections and simultaneously consider their surroundings. Barack Obama's portrait shares similarities with seating compositions of other former U.S. presidents, such as Abraham Lincoln, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, and George W. Bush.

However, there are notable differences, like Wiley's innovative interpretation of the official portrait, which includes floral symbols associated with Obama's life: chrysanthemums for Chicago, jasmine for Hawaii, African lilies for Kenya, and roses for love. Readings of labels or participating in guided tours are elements of an interactive experience that extends beyond technology.

The same applies to reflection. Engaged security personnel can attest to the genuine camaraderie among visitors when they pose for photos before the paintings and take turns doing so. Group discussions, teachers giving lectures, strangers eavesdropping on commentary, and often joining in – it's a networked and unplugged phenomenon that offers emotional authenticity in a world of relentless feedback loops and "techno-anxiety" that adds to the allure. As Harvard historian Jill Lepore mentioned in an interview with the museum's Portrait Podcast, visitors find it enjoyable to observe others' reactions to the portraits for the first time.

At one time, I questioned myself about the technology in the National Portrait Gallery, feeling it should be more advanced than that of my colleagues. However, while walking through the museum, it occurred to me that the lack of technology may strengthen boundary-experiences and help us leave our "digital selves" behind, enabling us to connect with our "inner selves" and others. People interact.