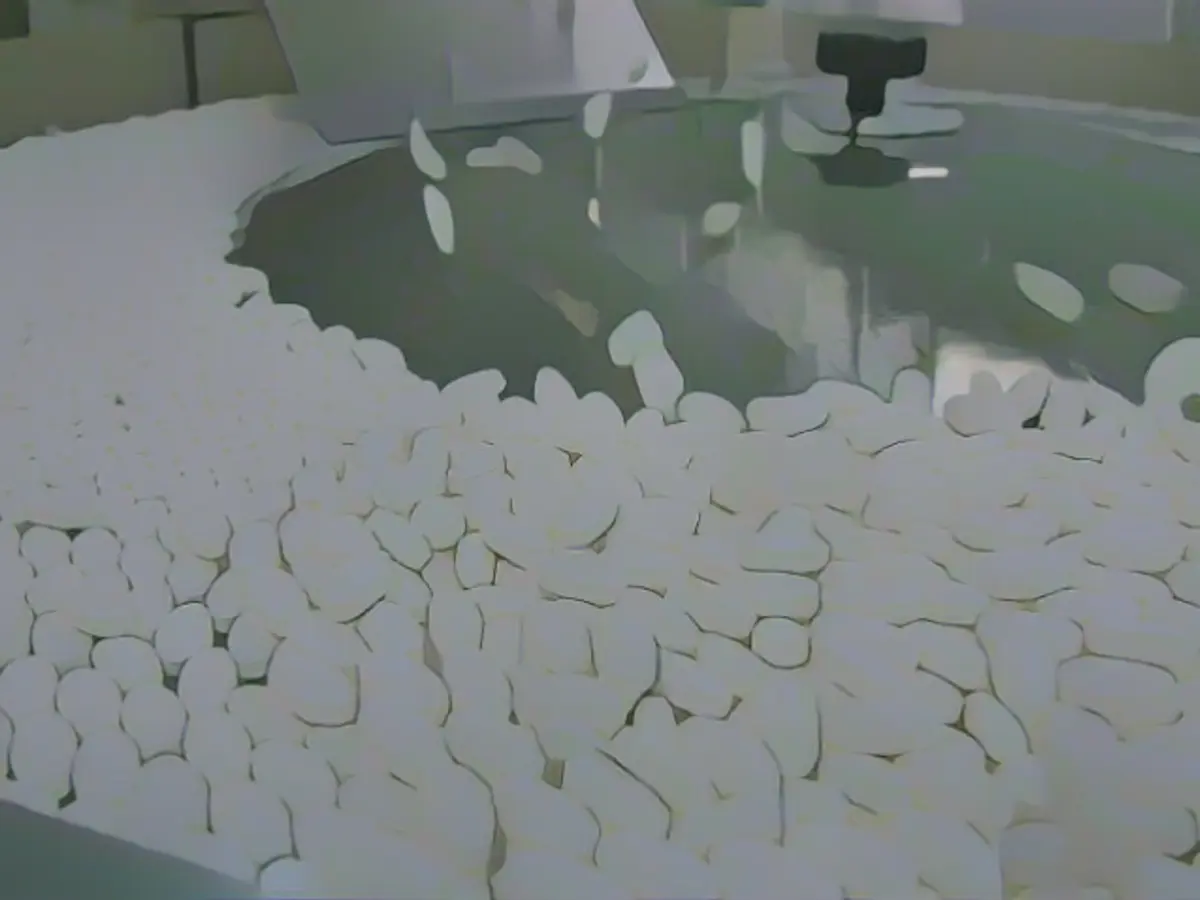

Drug shortages in the U.S. are forcing Americans to make difficult choices, experts warn Senate committee

"The shortage of generic medications like Fludarabin could literally mean life or death," Westin told members of the Senate Finance Committee during a hearing on Tuesday.

According to the investigation being conducted by the committee, record-breaking medication shortages are a persistent problem in the U.S., a situation that has been going on for decades and is unique to the country.

Multiple senators shared stories of constituents who had been harmed due to shortages. Senator Marsha Blackburn pointed out that the Vanderbilt Medical Center in Nashville had to deploy over 100 staff members to handle the disruptions and mitigate their impact.

"This is becoming increasingly common in our healthcare system," said the Tennessee Republican on Tuesday.

Senator Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, stated that over 84% of the nearly 200 drugs with persistent shortages are generic versions, which have been on the market for decades. Since 9 out of 10 prescription medications in the U.S. are generics, shortages have significant health implications for the nation as a whole.

"These shortages can cause significant harm to a large number of Americans," said Crapo. "The average shortage affects at least 500,000 consumers and forces them to seek reasonable alternatives or even forego treatment altogether."

Many of these generics are used to treat cancer. Fludarabin, a reliable medication used in CAR-T cell therapy, is currently in shortage, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Fludarabin has been on the shortage list frequently over the past few years.

For Westin and his colleagues, patients with rapidly progressing, aggressive forms of blood cancer have no time to wait for medications to return to the market. The window for potential life-saving CAR-T cell therapy, which can only be achieved using Fludarabin, is narrow. Westin informed the committee that there is no alternative.

"My colleagues are forced to make impossible decisions, including which patients to prioritize for potentially life-saving treatments," Westin said.

"We know how to treat cancer, but shortages force us to make impossible decisions," Westin added. "We have life-saving medications and we have life-threatening shortages."

A significant portion of the problem with generics stems from the fact that they operate with razor-thin margins and typically make very little profit, which means few companies have an incentive to produce generic medicine. According to Crapo, the number of companies abandoning the market and discontinuing these medications has increased by over 40% compared to the number of new entrants.

Most generic production is outsourced to countries like China and India, which can lead to geopolitical issues and quality control problems, said Dr. Inmaculada Hernandez, Professor of Clinical Pharmacy at the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at UC San Diego.

"Our medication supply chain is heavily dependent on foreign manufacturing. This is a national risk to public health," Hernandez told the committee.

One possible solution, Hernandez suggested, is for the government to implement value-based purchasing, which would motivate large buyers of generics, such as pharmacies and healthcare systems, to purchase from manufacturers with more reliable supply chains.

Unfortunately, generic manufacturers are not required to disclose their supply chains, so buyers currently make their decisions solely based on price.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the country's largest pharmaceutical buyer, must be able to make purchases based on quality and supply chain reliability, not just price, to effectively address shortages, said Marta E. Wosińska, an economist and Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution.

"If we start rewarding reliability, manufacturers can actually maintain higher prices because reliability is being rewarded. This would create incentives for more companies to enter the generic market," Woszinska tested before the committee on Tuesday.

In other words, more companies would join the generic market.

Senator Ron Wyden, D-Ore., said another challenge the government must overcome is the concentration of generic purchasing in the hands of a small group of highly powerful intermediaries in the healthcare industry. Although generics can be profitable, the money typically goes to these intermediaries – pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and pharmacy wholesalers – and not to the manufacturers themselves.

"There are many companies that produce generics, but they must compete for the attention of highly integrated intermediaries in the healthcare system," Wyden said. He added that the three largest pharmacy wholesalers control over 90% of the U.S. pharmaceutical market.

"Generic drug manufacturers that secure contracts with these intermediaries do so by offering them what they want — often more than they actually pay for the medications," Wyden said.

With such low prices, companies lack the funds to invest in critical manufacturing capacity or high-quality equipment to produce more reliable, higher-quality medicines. "In fact, generics companies compete to reduce prices, which in turn leads to problems with supply chain reliability and plant closures," Wyden said.

These intermediaries have also been criticized for raising medication prices. In a study published in the medical journal JAMA on Tuesday, Hernandez and her co-authors stated that PBMs often charge pharmacies unjustifiably high fees for generics that can reach up to 10% of the acquisition cost. These excess fees are not returned to the customer, but rather kept by the PBM.

Hernandez told the Senate committee that among the Top 50 generic drugs covered by Medicare Part D, price increases of 1,000% or more have been recorded for 16 drugs. Aripiprazol, an antipsychotic medication, is sold in pharmacies for an average of 17 cents per pill; a PBM for Rite Aid paid $11.70 per pill, a 7,000% markup.

****

Sign up for CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Register here for results from Dr. Sanjay Gupta Every Tuesday from the CNN Health team. "At the end of the day, they end up paying much more than the pharmacy actually pays for the medication, let alone what the manufacturer gets," Hernandez said.

Hernandez suggested strengthening regulation over PBMs. "Legislation currently before the Senate would make it illegal for PBMs to engage in spread pricing, a practice in which a company bills payers and pension plans more for prescription medications than it pays pharmacies and keeps the difference," .

Woszinska and other experts agree that they will continue to advocate for legislation to address medication shortages until it becomes law.

"The concerning aspect of these shortages is that they are largely avoidable," said Woszinska.