Data accumulation drive by DOGE may potentially compromise the trustworthiness of future American statistical records.

Folks, we're dealing with a hot mess at the U.S. Census Bureau and other federal statistical agencies. For decades, declining public participation in surveys and trust in the government have been a thorn in their side. But now there's a whole new complication: the Trump administration's murky data handling sparking investigations and lawsuits.

And current and former employees say this has become one of the reasons folks are shying away from sharing their info for the federal government's surveys. A former field rep shares they've encountered a lot of suspicion from households they tried to interview earlier this year, with some homes mentioning Elon Musk directly. And a current field rep feels less comfortable asking questions for surveys, with some people she'd previously interviewed mentioning their concerns about DOGE when they declined a follow-up interview.

"It's a system that runs on trust, and the trust, I would say, has been declining," says the current field rep. "It makes me sad as an American that distrust is at that level. But I do understand it. I fear for the data I'm collecting. Is it going to be misused? And the privacy guarantees that I describe to people - are those going to be respected?"

Nancy Bates, a former senior researcher for survey methodology at the bureau, knows the struggle all too well. She's tracked declining public participation in the census going back to the 1990s. Federal law prohibits the bureau from releasing information that would identify a person or business to anyone, including other federal agencies and law enforcement. But a report Bates helped prepare during the first Trump administration found 28% of people surveyed in 2018 said they were very or extremely concerned the bureau wouldn't keep their 2020 census answers confidential.

"Even prior to DOGE, the Census Bureau was always dealing with a level of mistrust about privacy and confidentiality," says Bates. "I absolutely can see why the public concern would be increased following these unauthorized and illegal access to data."

In several legal battles, plaintiffs have claimed Trump officials violated data privacy protections and did not provide clarity on who has accessed data and for what purposes. Critics of the administration's efforts worry about increased risks of government data systems getting hacked and unauthorized releases of people's personal information, leading to identity theft and other harm.

"The public doesn't do a great job of differentiating between federal agencies, so they may think that if DOGE is getting access to Social Security, IRS, Treasury, then they're probably getting access to the Census Bureau data as well," Bates says.

And that, Bates fears, could hurt the bureau's ability to produce accurate statistics.

White House spokesperson Kush Desai said in an email that "a small group of people refusing to engage with Census field representatives is not a new development" and that extrapolating "some widespread distrust of the Census because of DOGE is a hard stretch."

But experts warn that public concern about the Trump administration's push to access and compile existing government data could have long-term consequences on future data needed to redistribute political representation, monitor the health of the U.S. economy, allocate federal funding for public services, and better understand the needs of the country's people.

Skewed Statistics Ahead?

About a quarter of the people the bureau surveyed in 2018 said they were very or extremely concerned that their 2020 census answers would be shared with other government agencies or used against them. This divide could lead to a statistical phenomenon known as nonresponse bias, where certain populations decide not to participate in surveys, skewing the data and reducing its accuracy.

Federal statistical agencies have long struggled to fully reflect Black, Indigenous, Latino, and Asian people in the data they release, with many undercounting people of color while overcounting white people who did not identify as Hispanic. And the monthly jobs report has limited breakdowns by race and geography due to insufficient survey sample sizes.

"I would expect the problems that we already have with collecting information from marginalized communities would get worse if fears about the government having access to anything that people tell a statistical agency get worse," says Katharine Abraham, an economist at the University of Maryland who led the Bureau of Labor Statistics during the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations.

Data Centralization Threatens a Solution to Declining Responses

One strategy for addressing declining participation in surveys is using existing government records to fill in the blanks in a person's demographic profile. However, the Trump administration has not laid out "clearly specified purposes that Congress has authorized" or "clear protocols for how that information is going to be protected from unauthorized uses."

In explaining the decision to temporarily block the Social Security Administration from giving the DOGE team access to people's personally identifiable information, U.S. District Judge Ellen Lipton Hollander noted the Trump administration has "not provided the Court with a reasonable explanation for why the entire DOGE Team needs full access to the wide swath of data maintained in SSA systems."

"The purpose in the DOGE world seems to be very much to go after individuals," Abraham says. "Whereas if you're talking about the statistical agencies, that's not the purpose at all. The purpose is to use the data to provide information that can guide policy."

Abraham chaired the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking that, at the bipartisan request of Congress and former President Barack Obama, considered whether the country needed a data "clearinghouse" that would permanently store confidential survey data and other records from multiple agency databases to help government officials and certain outside researchers evaluate federal programs and inform policymaking.

The commission rejected that idea out of fear that it "would create an attractive target for misuse of private data." Instead, it called for the creation of a "National Secure Data Service" that "brings together as little data as possible for as little time as possible for exclusively statistical purposes."

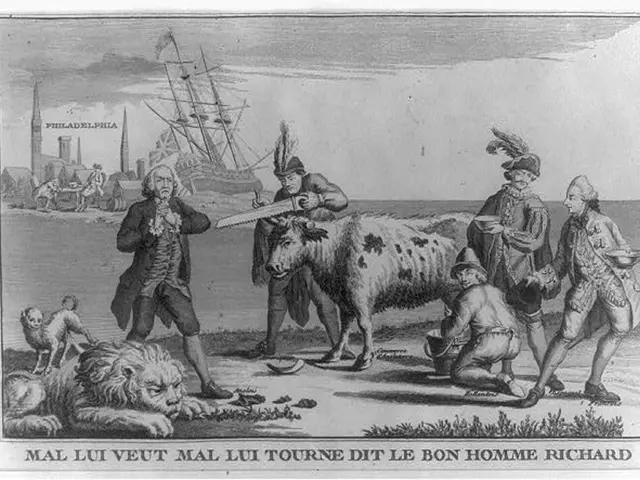

For Abraham, DOGE's push to pool government data brings to mind a controversial 1965 recommendation by social scientists. That proposal to build a national data center drew pushback from lawmakers concerned about privacy protections. At a 1966 congressional hearing, Vance Packard, an author who wrote about privacy threats, testified: "My own hunch is that Big Brother, if he ever comes to these United States, may turn out to be not a greedy power seeker, but rather a relentless bureaucrat obsessed with efficiency."

"We've been down this path before," Abraham explains. "[The 1965 proposal] raised so much alarm that it led to the passage of the Privacy Act." That 1974 law is cited in many of the lawsuits against the Trump administration's data push.

Abraham says she's concerned that DOGE's efforts will lead to a similar backlash and changes in law that overly restrict how government records can be used. "That could become a barrier to [the statistical agencies] being able to use the data, which I think would be unfortunate. Using administrative data instead of collecting survey data reduces the burden that the statistical agencies put on people, and, in a lot of cases, it leads to more accurate information."

Barry Johnson, a former chief data analytics officer at the IRS, also fears advances in the statistical use of government records will stall. "What's going on now will make it harder to make a credible argument that data are being used in a way that protects privacy and is really just for statistical purposes, to try to improve the way government functions."

Jeff Hardcastle, a former demographer for the state of Nevada, says some state officials who manage their governments' records are wary of how the Trump administration is handling federal data. That could complicate any new efforts by the bureau to request access to state records for the 2030 census. "You're going to have some states be reluctant to participate. And then you're going to have others that are very eager to participate," Hardcastle says. "This could contribute to inequalities across the country for the census count, which will be problematic in terms of redistricting and the impact on any funding formulas that are based on population size."

For Bates, the survey methodologist who retired from the Census Bureau, it all means her former colleagues who are still at the agency will likely have their work cut out for them as they continue preparing for the 2030 census while carrying out ongoing surveys. "This is like a tsunami, if you will, of pushing the public to have higher mistrust levels. I think it's going to take years, to be honest, to get back to where we were."

- The current field rep expresses concern about the declining trust in the government, fearing that the data collected may be misused.

- Katharine Abraham, an economist, expresses concern that increased public mistrust about government data handling could worsen existing issues with collecting data from marginalized communities.

- Barry Johnson, a former chief data analytics officer, fears that the current situation could make it harder to make a credible argument for the use of data in a way that protects privacy and is solely for statistical purposes.

- Jeff Hardcastle, a former demographer, anticipates that state officials may be reluctant to participate in future census efforts due to worries about how the Trump administration handles federal data, potentially contributing to inequalities across the country.