Conservation haven Niassa fell under ISIS's attack.

Revamped Report on Niassa Crisis: A Conservation Nightmare

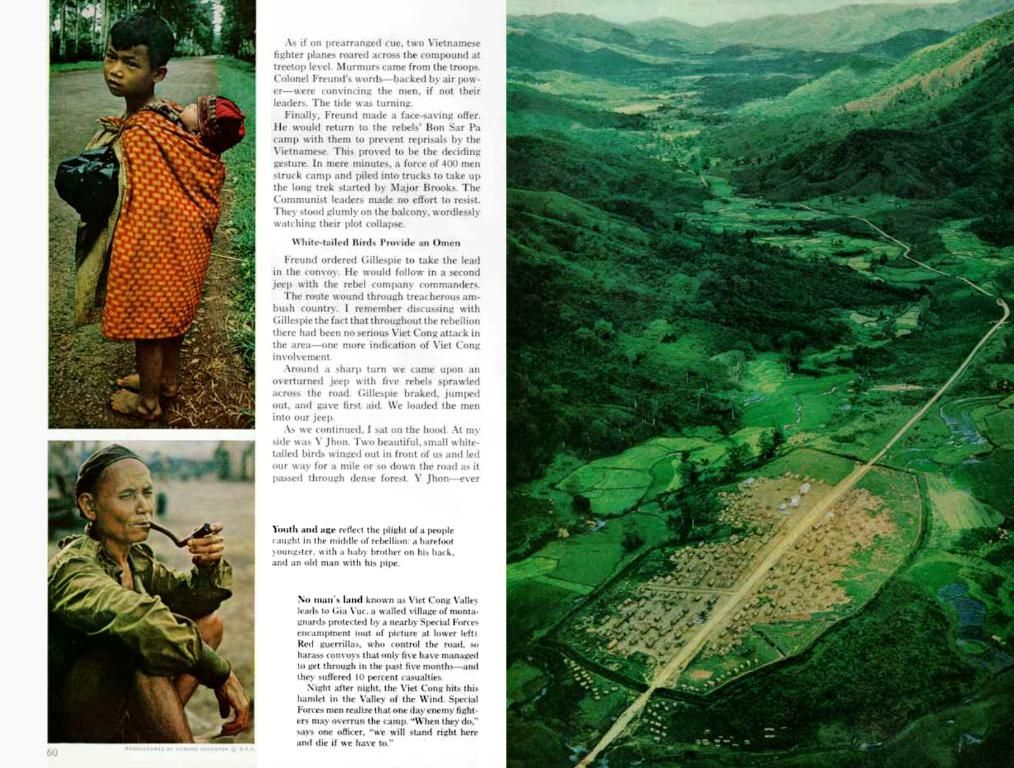

The tranquil evening of April 29 transformed into chaos for Colleen Begg, a conservation ecologist, as her phone buzzed with a WhatsApp message. The explosive news was an attack on the Mariri Environmental Centre she had established in Mozambique's Niassa Special Reserve by terrorists. Over two thousand villagers had fled into the wilderness, and five of Begg's ranger scouts were missing. A once-thriving conservation dream now hung precariously on the brink of collapse.

Over a month later, the situation in Niassa remains dire. Death tolls from recurring attacks have risen to at least ten, with numerous injuries and missing individuals. Each day, the threats to decades of painstaking conservation work and promoting economic growth intensify.

The Niassa reserve has been partially sealed off, with the Mozambican Army patrolling for Islamic State insurgents. Economic and business models have crumbled as families flee for safer territories, and tourism operators scramble to salvage their operations while managing the damage. Across the Lugenda River, nine conservation and tourism camps, along with 22 scout posts, now stand deserted. The United Kingdom and the U.S. State Department have issued travel warnings for Mozambique. Begg, who heads the Niassa Carnivore Project, beerily notes the devastating impact the attacks have had on tourist revenue: "Visitors won't come." Years of essential conservation work teeter on the verge of being undone.

Established as a hunting reserve in 1954 under Portuguese colonial rule, Niassa was transformed into a protected area in 1999 after multiple years of civil war. Unlike other African reserves, where a so-called fortress conservation mentality—prioritizing animal conservation over local communities—often governs, the Niassa reserve boasts a thriving human population that has coexisted with animals since time immemorial.

Some 70,000 people reside across 47 villages scattered within an expansive, fenceless wilderness covering over 17,000 square miles. The reserve accommodates the highest concentration of wildlife in Mozambique, including thriving lion, elephant, hyena, wild dog, and honeybee populations. The 17 conservation and tourism concessions spread across the reserve cater to various tastes, encompassing everything from budget eco-tourism to luxury safaris and sport hunting operations.

Agostinho Jorge, the director of conservation for the Niassa Carnivore Project, spoke of the deeply emotional impact of the attacks: "The most painful part was the suffering of the communities. It's one of the poorest areas in Mozambique, and the last thing we'd want is for the area to get destabilized from these attacks."

Most locals in Niassa engage in subsistence farming and fishing, and conservation is by far the largest employer in the district. The attacks occurred just days before the year's maize harvest, denying locals the benefits of their crop's yield. Over the years, conservationists and authorities have worked hand in hand to devise extensive anti-poaching regulations, encourage alternative revenue streams, and foster community tourism camps. "Now, all of that is gone," laments Begg. The annihilation of the reserve's annual million dollars in tourist revenue has led to the cancellation of many trophy hunter bookings. "I'm worried about the wildlife," says Jorge. "If these areas aren't protected, the numbers will start to dwindle should this situation persist."

Before the April terrorist attacks, conservation in Niassa had flourished. In recent years, the reserve's lion population had grown to between 800 and 1,000 animals, one of only seven populations of that size remaining in Africa. Elephant herds, which had been decimated by a poaching crisis spanning a decade, began to recover. Niassa is home to over 350 African wild dogs and honeyguide birds, exemplifying a remarkable symbiotic relationship between the species. "In Niassa, people and wildlife not only coexist but cooperate," explains Claire Spottiswoode, an evolutionary ecologist leading a research project in collaboration with the Mariri Environmental Centre and Mbamba village for over a decade. "It's one of the few remaining places where the unique cooperative partnership between people and honeyguide birds still thrives."

The insurgency terrorizing northern Mozambique since 2015 can be traced to the origin of these attacks. ISIS-M, as the group is known, has sought to gain territory, attract new recruits, and instill fear through synchronized onslaughts across the region. Their strength peaked in 2021 when their fighters were estimated to number around 3,000. South African and Rwandan forces responded with fierce counter-attacks, significantly reducing the group's size and strength. Regrettably, by mid-April of this year, militants resurfaced, targeting several small villages near Niassa's eastern border.

"ISIS-M has demonstrated remarkable adaptability," notes Nicolas Delaunay, the International Crisis Group's senior analyst for Mozambique. "We can see the building blocks of a multi-faceted strategy." On April 19, they attacked the Kambako hunting safari, located across the Lugenda River from Mariri. The insurgents remained in the area for four days, pillaging food, fuel, and supplies before departing. Before leaving, they decapitated two local carpenters and torched the camp.

A unit of 21 Mozambican Army soldiers was deployed to Begg's camp as a precautionary measure. Begg secured Mariri by removing vehicles, computers, and aircraft but left a small team of 12 anti-poaching scouts behind to prevent looting. Still, the scouts were overpowered by a band of well-armed, masked insurgents who infiltrated the camp, shouting, "Allahu Akbar," on April 29. Upon Begg's orders, the scouts scattered into the bush. Insurgents murdered two scouts and six soldiers that fateful day.

One member of Begg's team, Mário Cristovão, miraculously arrived at the camp on the day of the attack. Insurgents shot him three times, but he managed to crawl into a grove of tall grass to hide. He fashioned a makeshift splint for his legs and remained hidden for three days and four nights without sustenance or hydration, successfully fending off a hyena with the bloody boot of his left foot. He was ultimately rescued when the Mozambican Army returned to fortify the camp. "If I had slept, I would have died," Cristovão recounted to a Mozambican newspaper from his Maputo hospital bed last week.

Other organizations have rallied to help Niassa in recent weeks. "Decades of progress have been eroded, causing damage to both the wildlife and the human communities who call Niassa home," states Paul Thomson, senior director of conservation programs at the Wildlife Conservation Network. "We closely follow the situation, but with the instability persisting, potential threats to conservation, community safety, and tourism-based livelihoods continue to escalate. To sustain conservation efforts in the coming weeks and months, supporting local conservationists will be indispensable."

The disappearance of Begg's two missing team members casts a pervasive gloom over the conservation community. Yet, Begg and her colleagues persevere, providing financial support, food, and emotional encouragement to those they can assist. Begg sums up the spirit of determination driving conservation efforts in Niassa: "The only antidote to extremism is to keep going with conservation."

- The attacks in Niassa Special Reserve, once a thriving conservation dream, have led to a disruption in environmental-science research and wildlife conservation efforts.

- The community in Niassa, the largest employer in the district, has been hit hard by the situation, with crops going uneharvested and tourism collapsing, threatening their primary sources of income.

- The crisis in Niassa has also impacted the general-news landscape, as reporting on the region's war-and-conflicts intensifies, shifting focus from everyday issues such as sports and crime-and-justice.

- The history of Niassa Reserve, originally established as a hunting reserve under Portuguese colonial rule, has been marked by periods of civil unrest, leading to its transformation into a protected area in 1999.

- The insurgency in northern Mozambique, traceable to 2015, has disrupted the fragile ecosystem and nature of Niassa, with the Islamic State insurgents posing a significant threat to the wildlife populations.

- Science and politics have become intertwined in the Niassa crisis, as international bodies, such as the United Kingdom and the U.S. State Department, issue travel warnings based on the political instability caused by the insurgency.

- Amidst the chaos, the community in Niassa has shown resilience, with conservationists like Agostinho Jorge and Colleen Begg rallying support for the persistence of conservation efforts in the face of adversity.

- Accidents, such as the attack on the Kambako hunting safari, have further exacerbated the crisis, bringing devastation to the tourism industry and causing a ripple effect across the ecosystem.

- Archaeology, although not directly impacted, may lose valuable opportunities for research as the uncertain political climate in Niassa could discourage scholars from visiting the area, potentially leading to a loss of historical data.

- The conservation work in Niassa is not just about preserving wildlife, but also about fostering a harmonious coexistence between the community and the wild species, a testament to the incredible relationships between various species in the area, such as the unique partnership between honeyguide birds and wild dogs.