Chemical agents such as Agent Orange and Napalm destroyed Vietnam's forests and mangroves during war times, and the lasting damage is still evident today.

The long-term ecological consequences of the Vietnam War continue to plague Vietnam, with extensive dioxin contamination persisting in soils, waters, and ecosystems even 50 years after the war ended. This is despite the widespread environmental damage caused by over 70 million liters of herbicides sprayed, including Agent Orange, which contaminated about 2.9 million hectares of farmland and forests [1][5].

The ecological scars of the Vietnam War are evident in devastated mangrove forests, loss and fragmentation of biodiversity-rich rainforests, and persistent dioxin contamination that enters food chains and affects human health. International treaties aimed at protecting the environment during conflict have failed to enforce effective post-war environmental restoration in Vietnam [1].

In contrast, the environmental impacts of recent conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East involve a complex array of pollutants. Modern warfare has produced a spectrum of pollutants including fine particulate matter (PM 2.5), black carbon, sulfur dioxide, heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, microplastics, and radionuclides. These contaminants arise from burning fuel depots, bombardment of industrial zones, and wildfires triggered by conflict, leading to acute air pollution and long-term health consequences that extend beyond conflict zones [3].

In Ukraine, large-scale war-driven wildfires have released approximately 163 million metric tons of emissions, contributing to severe air pollution. In Middle Eastern conflicts such as Syria and Gaza, bombed industrial zones create dense plumes of unmonitored toxic chemicals that affect both local populations and cross-border environments, exacerbating respiratory and chronic illnesses [3].

While Agent Orange’s damage was primarily chemical contamination of soils and ecosystems with very long-lasting dioxins, conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East produce a broader spectrum of toxins affecting air quality and dispersing rapidly, but with ongoing risk from heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants as well [1][3].

The Vietnam War serves as a reminder that failure to address ecological consequences during war and after can have long-term effects. However, political will to ensure these impacts are neither ignored nor repeated is in short supply. An international campaign is underway to amend the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court to add ecocide as a fifth prosecutable crime alongside genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and aggression.

Remediation efforts for Agent Orange contamination have been slow and limited, with the first remediation agreement between the U.S. and Vietnam occurring in 2006. The treatment of 150,000 cubic meters of dioxin-laden soil at a cost of over $115 million was a significant step, but further work is at risk due to the Trump administration’s near elimination of USAID [2].

The legal situation regarding ecological damage during wartime is complex, with only limited compliance of treaties such as the Geneva Conventions and the 1980 protocol restricting incendiary weapons. Vietnam, Russia, and Ukraine have ecocide laws, but these have not prevented harm or held anyone accountable for damage during conflicts.

Current-day scientists are using satellite imagery to identify fires, flooding, and pollution, but on-the-ground monitoring is often restricted or dangerous during wartime. Forest restoration efforts in Vietnam were hampered by shoestring budgets and a focus on planting exotic trees instead of restoring natural forest diversity.

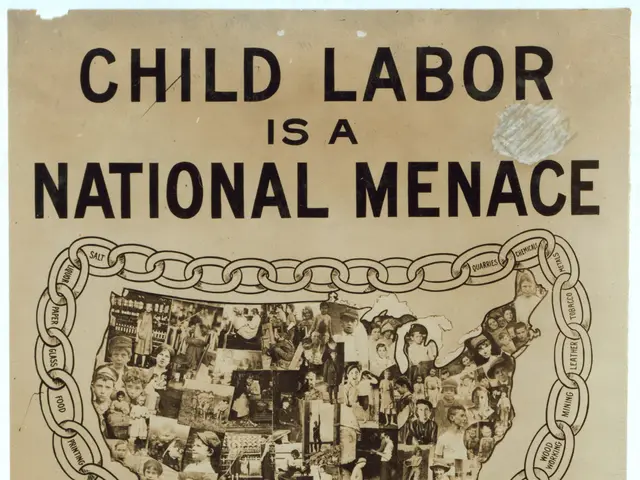

The U.S. first sent ground troops to Vietnam in March 1965 to support South Vietnam against revolutionary forces and North Vietnamese troops. The U.S. military turned to environmental modification technologies, including Operation Ranch Hand, to fight an elusive enemy operating clandestinely at night and from hideouts deep in swamps and jungles. The term "ecocide" was coined in the late 1960s to describe the U.S. military's use of herbicides like Agent Orange and incendiary weapons like napalm during the Vietnam War.

More than half of the spraying involved the dioxin-contaminated defoliant Agent Orange. Incendiary weapons and the clearing of forests also ravaged rich ecosystems in Vietnam. The U.S. imposed a trade and economic embargo on all of Vietnam after the fall of Saigon in 1975, leaving the country both war-damaged and cash-strapped. After these infernos, invasive grasses often took over in hardened, infertile soils.

In summary, the Vietnam War’s long-term ecological consequences are characterized by persistent dioxin contamination and stalled restoration efforts, reflecting a historical failure to adequately address wartime environmental damage. Meanwhile, contemporary conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East highlight the evolving complexity of chemical pollution in modern warfare, with acute air pollution and multifaceted toxic exposures. Both cases underscore the global challenge of insufficient political will and inadequate mechanisms to remediate war-driven environmental harm [1][3].

Read also:

- Germany's three-month tenure under Merz's administration feels significantly extended

- United Nations Human Rights Evaluation, Session 45: United Kingdom's Statement Regarding Mauritius' Human Rights Record

- Hurricane-potential storm Erin forms, poised to become the first hurricane in the Atlantic Ocean this year.

- Socialist Digital Utopia with Zero Carbon Emissions: A Preview, Unless Resistance Arises