In the face of promising data, experts remain cautiously optimistic about Lecanemab, a costly experimental Alzheimer's drug that showed a nominal reduction in cognitive decline in a Phase 3 trial. However, critics argue that the study may be biased due to the placebo effect, as only those who received the active drug were informed they were receiving it.

So, what's special about Lecanemab this time around?

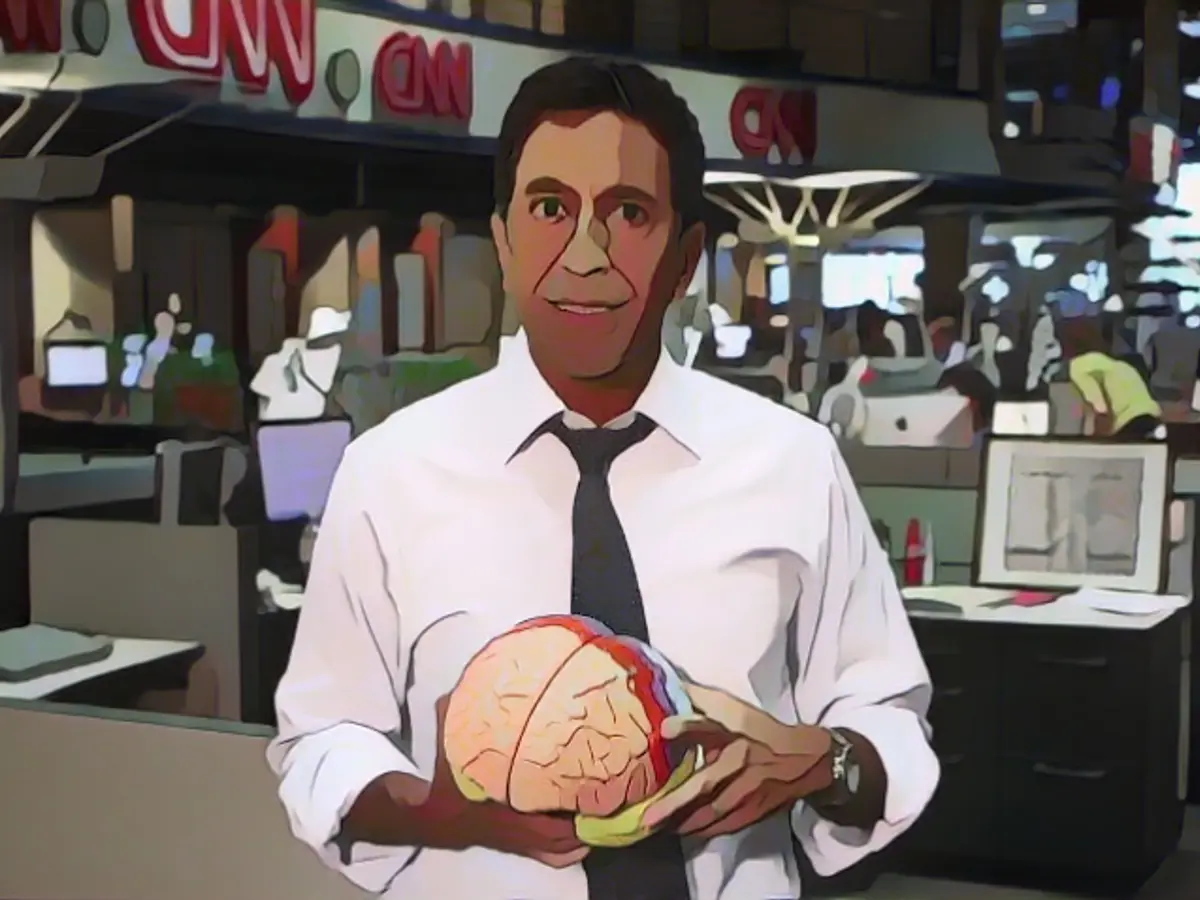

Statistician spoke, suggesting that Lecanemab is the 16th medication developed to eliminate toxic amyloid plaques in the brain. Many other products have worked as advertised, removing amyloid, but they've demonstrated little to no real benefit for patients. This has left many experts questioning the field's validity.

Lecanemab, however, seems to buck the trend. What makes it different? Is there something unique about this medication, or did the companies testing it conduct their clinical studies more intelligently, eventually uncovering the potential of such a drug?

"It's a mix of both," says Dr. Michael Irizarry, Eisai's Deputy Clinical Leader for Alzheimer's and Brain Health.

When planning clinical studies, researchers can leverage technological advancements, such as new scans that confirm the presence of Amyloid-Beta in the brain, Irizarry explains. Previously, doctors could only detect Amyloid plaques during an autopsy.

Moreover, recruiting participants in the early stages of the disease, where medications like Lecanemab might offer some benefit, was a strategic choice.

"We make sure we recruit people who are motivated and likely to respond to the medication," Irizarry adds.

Additionally, lessons learned from past failures, such as Aducanumab, helped Eisai select a large enough study population (around 1,800 participants) to show a clear difference between the medication group and the placebo group.

The Phase 2 study also allowed the dosage to be carefully chosen, ensuring all participants, randomly assigned during the trial, received the same dose.

Ultimately, Lecanemab binds to amyloid protein fragments, preventing them from forming fibrils, the origin of plaques in the brain. An early amyloid recognition could have additional implications.

Waiting on Further Data

While some independent experts express skepticism about the study's results as a significant breakthrough, others believe it represents a successful strategic approach by the drug companies developing the technology which allowed them to conduct a large-scale study detecting small impacts.

Dr. Constantine Lyketsos, psychiatrist and professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, is not convinced that this drug brings anything new to the table. "I don't think we'll see any other clinical benefit than Aducanumab," he says.

Aducanumab (branded as Aduhelm) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in June 2021 despite reservations from the external advisory committee. Potential benefits in some studies appeared modest, and Medicare only agreed to cover the medication under specific conditions. Despite these efforts, Aducanumab became a commercial flop.

The primary difference between the two studies, according to Lyketsos, is the study's larger sample size for Lecanemab. If we compare the results of Lecanemab to Aducanumab, which showed positive results in some studies, we'd see the same benefits.

Lyketsos is also concerned about ARIA, an amyloid-associated brain scan anomaly, which was observed in other types of Amyloid-clearing antibodies, and occurred in approximately half of the participants in the Lecanemab trial.

These protein fragments, targeted by the medication, tend to coat the walls of the brain's blood vessels. When these blood vessels disappear, fluid or blood may enter the brain. If a large enough leakage is present, it will be visible on an MRI.

While some individuals with ARIA show no symptoms, others can lead to hospitalization or long-term damage. Experts are not yet clear about what happens when mild ARIA appears and disappears, or how often catastrophic cases of swollen brain occur, Lyketsos warns.

If only a few thousand people received Lecanemab injections, the sample size might not be big enough to determine if severe cases of brain swelling occur as infrequent events.

"Perhaps there isn't any catastrophe. We just don't know," Lyketsos concludes. "If many drugs like this hit the market, we'd have a big asterisk for indicating that we truly tried it." He couldn't comment on the drug's long-term safety.

Like Lyketsos, activists question the drug's feasibility in making it available to patients.

"If it were just a pill, if it wasn't so expensive, I might try it," he admits. But considering the potential costs – similar to that of Aducanumab, which currently costs around $28,000 for a year's worth of treatment – and the minimal reduction in disease progression, it's unlikely to be practical.

The price of Lecanemab is yet to be determined following FDA approval.

Lyketsos adds that there may be exceptions if the analysis of clinical studies indicates that certain groups of people benefit more from the medication than others. Eisai spokesperson Irizarry says the company is currently analyzing study results in this regard – whether in those with a genetic risk of Alzheimer's or with complex health conditions like diabetes or hypertension – and how treatments impact them. Reactions could vary.

"That's definitely an area we're working on," Irizarry says.