A weekly grind of four days isn't such a pipe dream for UAW workers, says union president Shawn Fain. Although it hasn't come to fruition yet, not in this round, the idea is far from impossible. It was once a Union's ambition in the mid-century when they were granted nationwide representation for auto workers.

Fain believes that the four-day week is a realistic goal. Despite automakers rejecting the proposal, he's pushing to reboot the conversation on recouping lost time for workers. This dream, once shared by Fain's union predecessors, is well within reach, he claims.

But the auto manufacturers have a different take. Ford CEO Jim Farley stated that approving the four-day week would result in excessive losses for the company. He hinted at factory closures and mass layoffs if the automakers agreed.

The collective bargains reached by unions and automakers resulted in limited discussions about the four-day week, effectively putting an end to the negotiations. The Union emerged victorious, securing a record-breaking contract with immediate 11% wage hikes, further 14% wage increases over the contract term, COLA adjustments, improved pensions, and various other benefits.

With average hourly wages of $43, the majority of workers at GM, Ford, and Stellantis will earn at least $1,700 weekly, given a standard 40-hour workweek. Given the potential for COLA adjustments, their wages could even surpass this figure. The wage structure for an alternative contract with a four-day week remains unclear. However, employers would have to shoulder additional 25% wage hikes for the 32-hour workweek plus the recently agreed upon wage increase.

The companies' ability to achieve further growth relies on various factors, such as changes in productivity, vehicle demand, and pricing and material costs, which will have a significant impact on the automobile industry. While production costs outweigh labor costs (making up approximately 7 to 8% of the vehicle production cost), Farley argues that companies can only maintain profitability by keeping costs low at the expense of their employees.

Fain disagrees, pointing out the benefits of the four-day week in terms of workload adaptation due to the advances in technology such as AI. The better productivity could shorten the workweek, he suggests. However, the companies have consistently highlighted the fact that they can afford the existing contract terms, and there's still room for improvement, such as exploring a future four-day work week.

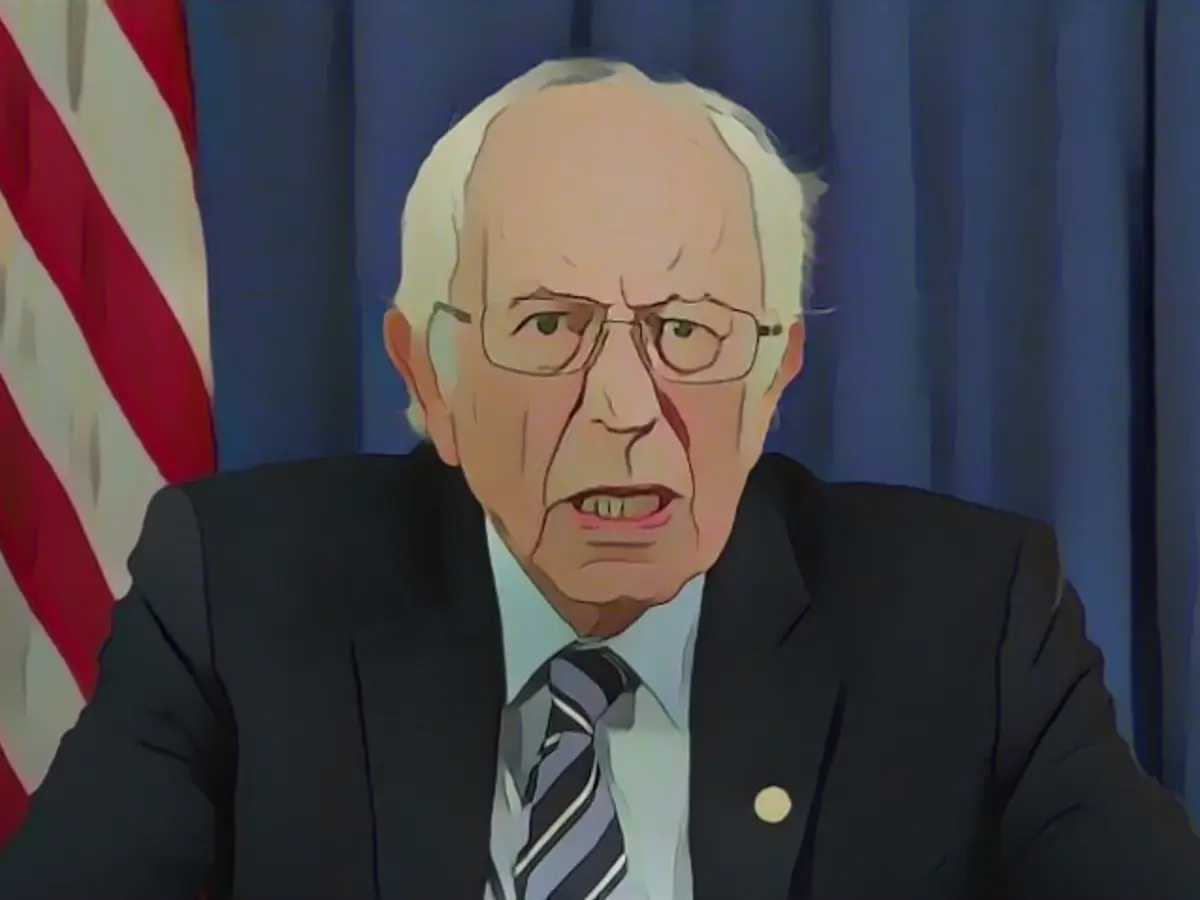

"The choice of these corporations and billionaire elites is to hoard all gains at the expense of fewer employees," Fain declared. He believes that instead of cutting jobs by improving productivity, companies should take advantage of technology. Fain believes the four-day week is indeed possible.

In fact, companies worldwide have been trying out the four-day work week concept. A recent global pilot project involving 33 companies and 903 employees showed no companies planning to revert to the traditional five-day routine, and the pilot participants gave an average score of 9 out of 10 for their overall experience.

Unilever, a global consumer goods company, rolled out the four-day week in New Zealand and Australia for its employees who wished to take advantage of it.

However, the 40-hour five-day work week has proved beneficial to unions as well.

Benedict Hunnicutt, a University of Iowa historian specializing in labor history, believes that unions played an essential part in setting the norms for the 40-hour five-day work week.

"Organized labor has always been the most significant force in demanding shorter working hours," he noted. He's convinced that the eight-hour workday movement caught on in the 1930s and eventually led to a nationwide push for a 30-hour workweek.

Despite early victories for the 30-hour workweek, economic pressures led to the demise of the reform. The push for shorter work hours became a trade-off for higher wages, which the unions accepted reluctantly.

Fain says that companies should invest in technology instead of cutting jobs to maximize profits. The Coronavirus pandemic and remote work have offered new opportunities to explore the four-day work week. However, factory closures and mandated overtime have made the four-day week an urgent concern for UAW workers.

"Seven days a week or even 12 hours a day working multiple jobs just to survive is no life," Fain said. "Workers need to take charge."

Credit to Vanessa Yurkevich and Anna Cooban from CNN for their contributions.

References:

- [The New York Times](https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/29